We’ve all gone swimming in the lakes and in the seas. We’ve all choked on that accidental gulp of water while swimming carefree.

But have we all looked under a microscope to see what these waters hold?

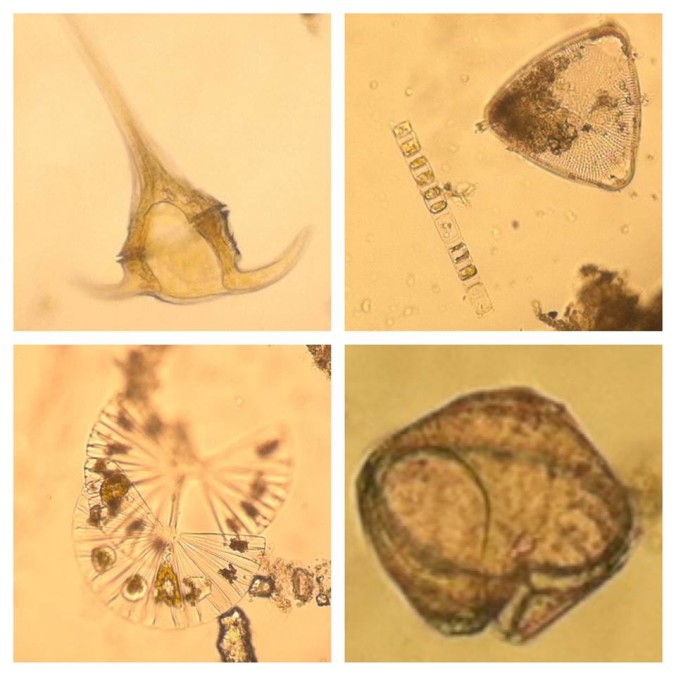

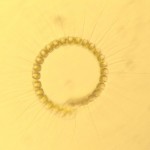

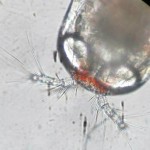

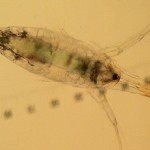

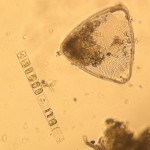

What you just saw were three plant-like organisms called diatoms, and the moving thing: a small larval crustacean called a nauplius. Makes you think differently about that next gulp of water you’ll take, doesn’t it?

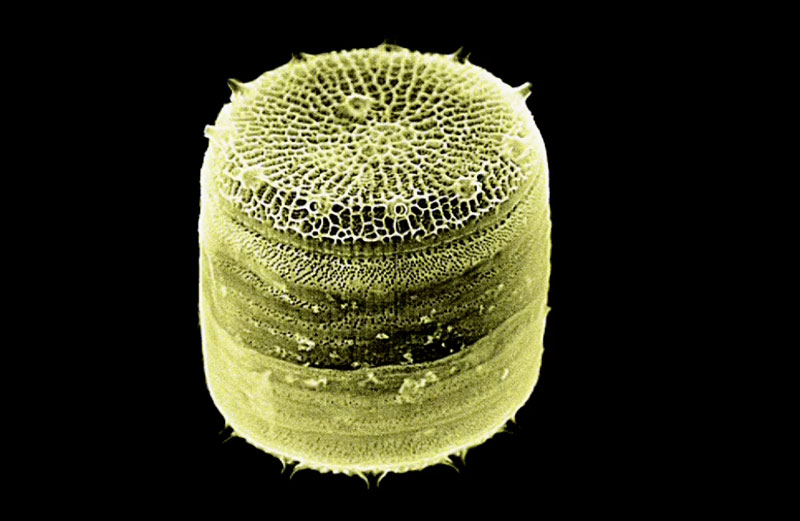

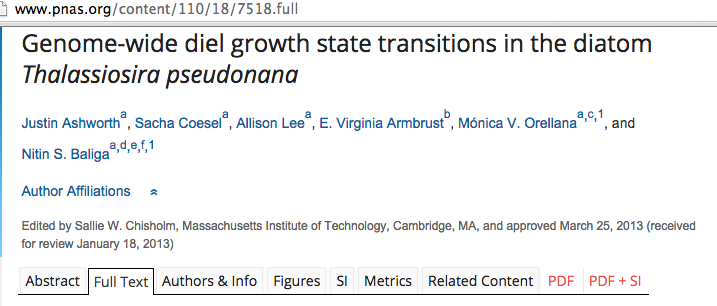

I had previously never given much thought to the invisible marine world until I was employed to work on a project researching the effects of climate change on micro-algae, particularly the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana.

Who is this Thalassio-whatchamacallit and why should I care? Let me ask you a question:

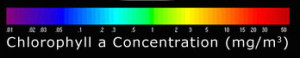

Where does the earth’s oxygen come from? Humans, as the terrestrial beings we are, will easily shout out, “The trees!” But did you know the trees are only responsible for producing about 30% of that oxygen? The algae and phytoplankton living in the water are responsible for the other 50-70%! That is more than half!! In addition, these amazing silicified (glass) microorganisms make up the base of the food web and are responsible for 40% of the ocean’s primary productivity. What an incredible hidden forest.

I will never look at the ocean in the same way.

Phytoplankton as Art

I learned of a man named Klaus Kemp, nicknamed The Diatomist, who also doesn’t look at the ocean in the same way. He sees magnificent beauty in the Invisible Forest and has spent his life mastering the Victorian art of creating kaleidoscope-like arrangements of diatoms.

I don’t think I could have the patience or attention span to do such painstaking technical arrangements under a microscope but don’t get me wrong, I do love a good microscope session attempting to photograph some of the world’s smallest organisms.

Capturing Invisible Things

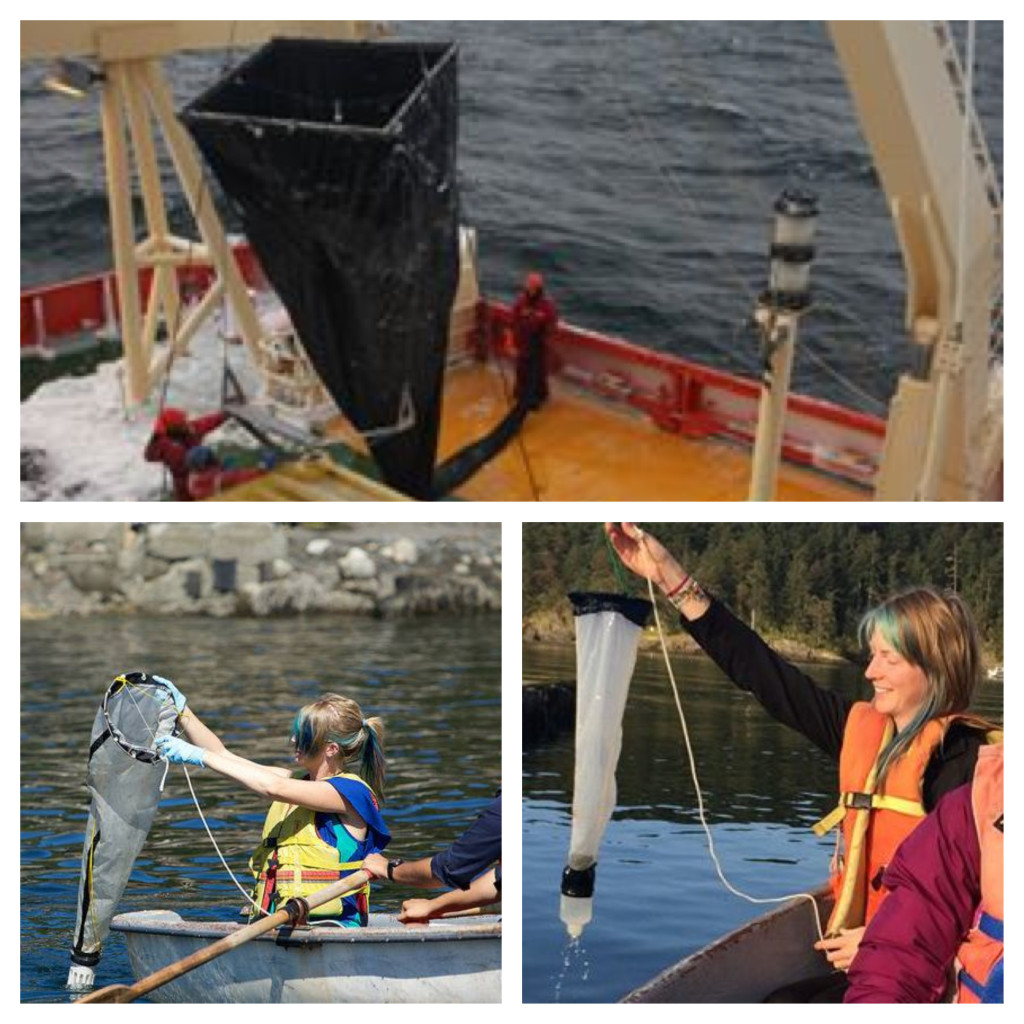

The best way to collect a large abundance of phytoplankton is to do a tow with a net that has a good funnel-shaped collection cylinder called a cod end. Some nets are huge and require winches to lower into the water. Others are more manageable and can be done by hand, towed behind a row boat.

Phytoplankton can range in size from 2 – 1000 microns. What does that even look like? If you run sea water through a mesh filter that had a 333 micron weave, you could see Coscinodiscus wailesii by eye; It looks like tiny grains of sand. Does that help the visual reference at all?

Unannounced Changes

For three weeks, from March 17, 2015 until April 3, 2015, I worked up in the Pacific Northwest’s San Juan Islands at the University of Washington Friday Harbor Labs. My boss and Co. were running ocean acidification experiments on our lab strain diatom, Thalassiosira pseudonana, but we wanted to also collect the wild plankton living in the harbor. Weekly we would take the row boat out to do a tow. I attempted to photograph what I saw using only an iPhone through the microscope:

Week 1: We saw many different types of diatoms: Thalassiosira, Melosira, Coscinodiscus, Chaetoceros, Ditylum, Thalassionema, Skeletonema, Cylindrotheca, & Corethron

Week 2: The diatoms had mostly been replaced with dinoflagellates (Protoperidinium, Dinophysis) and zooplankton, such as the crustacean copepods.

Week 3: The waters were teeming with copepods and tiny little jellies: Cnidaria and Ctenophora.

Week 4: Ctenophores had disappeared and a diverse collection of diatoms and dinoflagellates floated amongst a gazillion copepods. (Diatoms: Thalassiosira, Coscinodiscus, Ditylum, Chaetoceros, Odeontella, Thalassionema, Skeletonema, Bacillaria, Cylindrotheca, Triceratium; Dinoflagellates: Ceratium, Protoperidinium.)

While I would not spend hours arranging any of these into beautiful mosaics, I would spend hours trying to photograph them as they are.

Lab Diatoms Go Wild

What experiments are we doing with these critters at the Friday Harbor Labs that we can’t do back at the Institute’s labs in Seattle? Mesocosm Experiments. Mesocosms are a bridge between controlled laboratory experiments (which use artificially made sea water) and the more variable and uncontrolled field environment (which use natural sea water coming from the harbor). In 2011 the University of Washington invested money from grants, and private donors to build an amazing Ocean Acidification Environmental Lab with pimped out coolers that have the ability to monitor and control experimental conditions.

The sea water in this area is naturally more acidic due to freshwater river run-off, coastal upwelling and anthropogenic practices. The pH of the average ocean is said to be around 8.1 reflecting the average atmospheric CO2 levels at 400ppm. The pH of the waters at Friday Harbor is 7.8 with a recorded dissolved carbon dioxide level of 650ppm. We are using this water with all its organic goodies to test how our lab strain of Diatom will respond genetically to future predicted decreases in pH (due to increases in dissolved carbon dioxide).

Thalassiosira pseudonana is an algae that creates a silica glass shell. Because of this, they do not have the same need for calcium as corals, oysters and other shellfish do. This means when carbon dioxide dissolves into the sea water, snatching up available calcium, this particular organism doesn’t seem to suffer. In fact, with increase CO2 this diatom is able to relax its carbon concentrating mechanisms, passively allowing CO2 to dissolve through its glass frustule. In the process of photosynthesis, the ability for the plant to sequester much of the increased CO2, is referred to as CO2 fertilization. To read the final publication on what we found in the laboratory experiments click the paper below:

Breathe

Next time you take a deep breath, thank these under-appreciated organisms which make up the Invisible Forest and give us the oxygen we need to survive.

Want more?

To see more photos of the entire spring trip to Friday Harbor, click here:

To see photos from a previous fall trip taken in September 2014, click here.

Photo Credits:

Hsiao-Ching Chou: Allison wearing gloves holding net; Gloved hand holding cod-end; Mesocosms.

Spiro Jamie: Allison holding smallest net.

Allison Lee: All other photos except NASA chlorophyll distribution image and TEM image of Thalassiosira pseudonana.

Share this:

Recent Comments