When I was a new scientist starting work in the lab I purchased the book At the Bench, by Kathy Barker. It became a well-read manual I referred to when questions arose about living and working in the laboratory. As I gained experience over the years, moving into more responsibility overseeing high school and undergraduate interns, I bestowed upon them this same book for reference and peace of mind.

I had no idea that nearly a decade later I would have the chance to get to know the author.

We met at an event co-hosted by the Association for Women in Science (AWIS) and Hutch United at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. There was to be a discussion on Social Media and Activism in Science with distinguished panelists :

- Kathy Barker, PhD –Scientist, Author, ScientistsAsCitizens.org, @ScienceActivist

- Jennifer Davison –Program Manager, Urban@UW, @JenEDavison

- Sharona Gordon, PhD –Professor, UW Department of Physiology & Biophysics, @ProfSharona

As a young scientist active on social media, I wanted to hear the opinions of more advanced researchers and the voice they use online. (If you want to know my opinions, read this post.)

Kathy was the first person I met before entering the building. It was dark and raining, as per usual in Seattle, and we were both lost. Together we ventured in to what we thought was the correct building and as the house lights illuminated our faces I saw she had a streak of red dyed hair. As someone who sometimes worries about whether or not I’ll be taken seriously with my turquoise dyed hair, I was glad to see another scientist rocking the look.

Kathy has a PhD in microbiology and spent time as an assistant professor in the Laboratory of Cell Physiology and Immunology at Rockefeller. She currently consults and writes on science management and communicating science to society. She has authored two books At the Bench and At the Helm.

Kathy gladly agreed to participate in an interview to share with us her diverse set of experiences and gained wisdom:

What is your earliest memory of being hooked by science?

Volcanoes, animals, rockets, and infectious disease. There was scant information around in those pre-web days, but I devoured all the books in our little library.

What did you study during undergrad? Did you know what you wanted to study before beginning?

I was an English major for 2 years of college, with no interest in science. After dropping out for a few years to travel and work, I returned to college and got hooked by a tour in a basic biology class of a scanning electron microscope and a view of an insect eye. I ended up doing a double major in English and Biology.

What was your first science-related job?

Breeding mice as an undergraduate. I should have thought more carefully about animal use at that time, for it troubled me for the 4-5 years before I realized I should just say no to animal work.

How did you decide to go for a higher degree?

Entropy.

Did you have any preconceived notions about science, or scientists, and did that change once you explored your career in science?

Not knowing any scientists until I was in my 20’s meant I had a cartoon image of what a scientist was, and didn’t realize the absolute power I had to make much more informed and better choices. No one can tell you how to be a scientist. You get to be an activist, or take time off, or have no kids or a zillion kids (I had 3), or do “descriptive” science, etc etc.

Has your work allowed you to travel? If so, where have you gone and what were you doing there?

Yes. The writing turned into giving workshops on running labs, and I traveled all over the country. It is great fun, and I meet wonderful people.

Could you expand more on your experiences working in different sectors?

After my postdoc, I was an assistant professor for a few years. I found it interesting that many of the problems encountered by people in the labs were communication problems, and were common to all. I wanted to write about it, and contacted a publisher. He thought it was a good idea, and I left the lab about 6 months later to write.

Writing was hard at first. It took me a while to build up colleagues, and expertise, and until I had a finished product, my ego took a hit. I hadn’t realized how that title ‘scientist’ gives you a sort of pass in life, as people assume you are doing something valuable….even when it isn’t true.

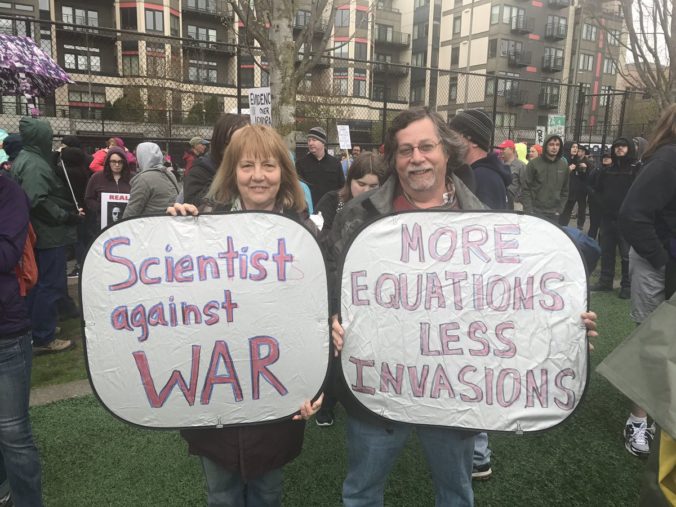

I’m currently hooked up with a group of public health academics, and together we are writing a book on the primary prevention of war. Three of my lives came together here: the scientist, the writer, and the antiwar/antimilitarism activist. It feels good!

Have you experienced any big compromises or struggles making a career in the sciences?

Compromises or struggles…I can’t quite come up with anything. Not everything went well, but that is probably because I wasn’t as thoughtful about my scientific life as I should have been, not about the field I was working in, or about my future.

What keeps you motivated when you’re feeling the drudgery? What keeps science FUN for you?

Even making buffers in a lab was fun for me- I loved everything about the lab, every single day. I never felt drudgery…except with writing. I wouldn’t say it is fun every day, but I am very happy.

Was there any one person that inspired you?

Not really. The big sister of the girl next door and a microscope, and I thought both she and the microscope were absolutely cool.

What are some inspirational materials you’ve used along the way?

Natalie Angier’s “In Search of the Oncogene” is one of the best books about how lab science is done.

What are some key points you wish you knew or that you remind yourself of during your science career journey?

I was too independent- I wish I had had a mentor. Even having a role model would have meant I was thinking about the strengths and weaknesses I had. It meant I would have known when I needed help.

What is your big dream?

I would love to be part of a movement that convinces scientists to think about war and nonviolence, and to choose their careers and paths with consideration of the effects of their work for all of society.

~~~

Thank you so much, Kathy, for sharing your career journey!

Make sure to follow Kathy’s newsletters and feed on Twitter.

Do you like the posts you see on Woman Scientist? Share them with a friend!

Want more interviews? We will post interviews with a new feature Woman Scientist every week, and in the meantime you can read from more inspiring women here.

Share this:

Recent Comments