My friend, Kate Ruck, told me to follow a woman named Ocean Allison on Instagram. “She is doing awesome podcasts about the Ocean, I think you would enjoy!” Of course, I hit ‘Follow’ and started listening. The first podcast I heard highlighted the work of Dr. Greg Rouse from Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Dr. Rouse is a marine biologist frequently discovering new deep sea species like bone eating worms, ruby sea dragons, and purple socks (curious? listen to the podcast!)

Allison has gone on to interview 48 and counting, other acclaimed ocean advocates such as: Dr. Wallace J Nichols (author of Blue Mind), Rob Machado (pro-surfer), Pam Longobardi (plastic pollution artist), and Jim Toomey (cartoonist of Sherman’s Lagoon).

With a background in Marine Biology, she now combines her knowledge of ocean science with her skills in communications in order to be a voice for the ocean.

“I consider myself a marine biologist since that’s what my background is in, but in reality I am an ocean science and conservation communicator. I strive to help scientists communicate their important ocean research to the public through education and digital media.” ~ Allison Randolph

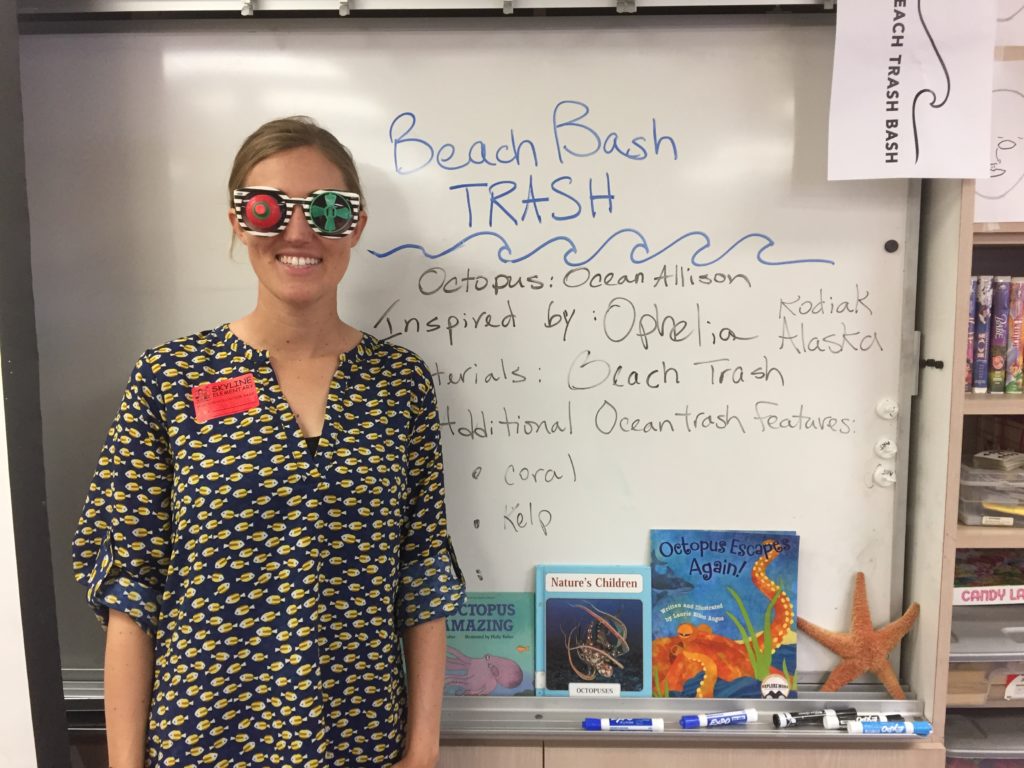

Teaching plastic pollution to K-6 students.

While earning her degree at Florida Institute of Technology she worked as a coral reef researcher in a Marine Paleoecology Lab and as an intern with Dr. Andy Nosal at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Allison has also worked as an educator at the Birch Aquarium in San Diego.

After traveling to Antarctica as the Outreach Specialist on a National Science Foundation expedition, Allison began to build her brand as Ocean Allison in order to educate the public on all things ocean via her podcast, social media channels, and educational programs. She is also currently working on a project with the San Diego Natural History Museum, and welcomes every opportunity to communicate ocean science and conservation topics.

Let’s hear more from Allison as she share’s her career journey:

What is your earliest memory of being hooked by science?

My love the ocean started before I can remember. My childhood revolved around the ocean and over time this interest turned into curiosity, but I don’t know if I ever really thought of this ocean exploration as science (even though it was!). Growing up, it seemed to me that science was something you did in school, and this subject always drew me in. I completed my first science fair project in third grade and continued to participate in science fair till my junior year of high school, making it to regional and state fairs several times.

What did you study during undergrad? Did you know what you wanted to study before beginning?

I majored in Marine Biology at Florida Institute of Technology (FIT) during my undergraduate degree. A big reason I chose FIT was because they have a great marine bio program, and this proved to definitely be true. Apparently, I knew I wanted to study marine biology as early as 1st grade. Six year old me used to go around saying, “I either want to be a chiropractor or a marine biologist”.

What was your first science-related job?

My first science-related job where I got paid was in the Marine Paleoecology Lab at Florida Tech during my undergrad degree. I was a student worker in the lab for three and a half years, helping to analyze climatic variability and upwelling regimes in coral reef cores from Pacific Panama, dating back to about 6,000 years before present.

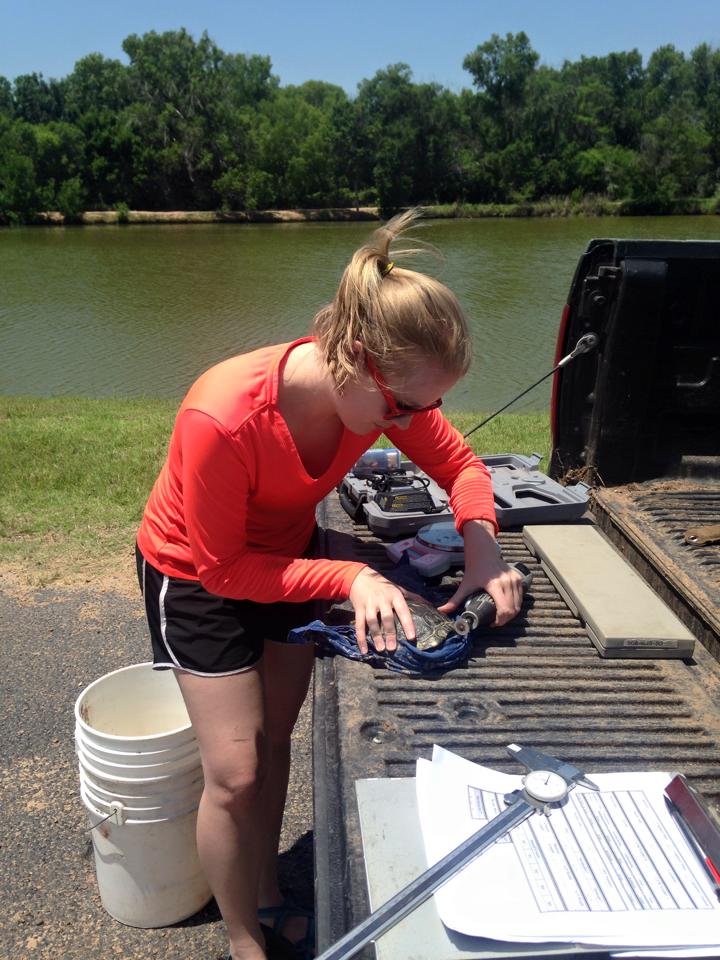

My first unpaid science-related job was as an intern with Dr. Andy Nosal at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, studying the biology and ecology of a large seasonal aggregation of leopard sharks in Southern California.

Shark survey cruise with NOAA SWFSC in Channel Islands.

What are your thoughts on getting a higher degree?

Thus far, I have not chosen to earn a higher degree. While I don’t rule it out, I have found that I see more opportunity in forging my own path rather than continuing on in academia.

Additionally, since a main focus of mine is science communication, it is actually important for me to be outside of academia so that I can see the big picture and relate to the public; while still of course maintaining a professional relationship with colleagues doing research at universities.

Did you have any preconceived notions about science, or scientists, and did that change once you explored your career in science?

Before entering college I thought that marine scientists spent majority of their time out in the field, researching their subject. After working in a lab and doing an internship in the field, it became clear to me that grad students and scientists were spending majority of the year analyzing data and writing papers and grants in the lab, with only a few weeks, to maybe a few months each year spent in the field collecting data.

Scientists are dedicated researchers that put in long hours to make sure that the results they present to the world are accurate and peer-reviewed. This both impressed me, and also made me realize, maybe my interests will steer me in a slightly different direction.

Has your work allowed you to travel? If so, where have you gone and what were you doing there?

Through my work I’ve had the opportunity to travel to some truly incredible places around the world.

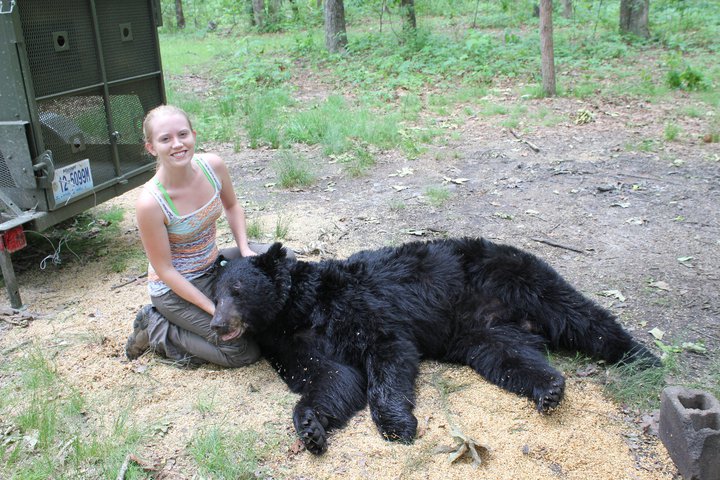

As an undergraduate I traveled to Indonesia for a research internship with Operation Wallacea. There I spent 6 weeks living on a remote island, diving twice a day, helping graduate students collect field data on various coral reef related research projects.

In 2015, I traveled to Chile and Antarctica as the Outreach Specialist on a National Science Foundation research expedition studying how climate change is effecting the ecology of Antarctic deep seafloor organisms. I wrote blogs, formed relationships with K-12 students, posted on social media, and produced a short documentary film about the expedition and it’s science.

A few months ago, I attended the BLUE Ocean Film Festival and Conservation Summit in Monaco where my film, Antarctic SeaScience Expedition, was awarded Honorable Mention.

I had the opportunity to meet some incredibly inspiring ocean filmmakers, conservationists, and scientists all working to create positive change for the ocean and the planet.

Over the last several years, my work has brought me to San Diego and surrounding areas in Southern California. I have worked on leopard shark research projects in La Jolla and on Catalina Island with scientists from Scripps, I have surveyed shark populations in Southern California waters with NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center, I have worked at Birch Aquarium as an informal marine science educator, and continue to work on a comparative fish skeleton collection project with the San Diego Natural History Museum.

Could you expand more on your experiences working in different sectors?

While I’ve had experience working in all of these sectors, some of which I personally preferred more than others, I am now working to bring them all together and highlight the positive characteristics of each. Regardless of what sector I want to work in, I find all of these (and more) vital and important entities in the world.

Through my podcast, Ocean Allison, I highlight individuals from any and all business sectors that are creating positive change for the ocean. In this way I am uniting people from all areas that are maintaining a common goal, just going about it in all different ways. You can listen to weekly episodes of my podcast by searching Ocean Allison on Soundcloud, Google Play, iPhone Podcast App and oceanallison.com.

Have you experienced any big compromises or struggles making a career in the sciences?

One of the biggest obstacles I came across when pursuing a career in science was when I realized that much of what science uncovers remains only within the scientific community.

What keeps you motivated when you’re feeling the drudgery? What keeps science FUN for you?

Earth is Blue! The ocean is the driver of our planet. Life came from the ocean. Our climate system is controlled by the ocean. Majority of our oxygen comes from the ocean. 99% of Earth’s biomass is in the ocean. It’s what makes our dot in the solar system unique. We need the ocean. We have abused it. And now, in order to help ourselves, we need to help the ocean.

Remembering all of the above, keeps me motivated everyday. These are the fundamental truths that inspire me to do science, to communicate science, to educate, and to document. Not to mention getting out in the water and enjoying all that the ocean has to offer, like SCUBA diving, snorkeling, surfing, swimming, and boating!

Snorkeling in the Bahamas.

Was there any one person that inspired you?

In terms of ocean curiosity and exploration, my parents were definitely my biggest inspiration growing up. They facilitated my ocean experiences and always were teaching me about ocean animals and ocean dynamics.

In school, my middle school science teacher Simone Flood was a huge inspiration. She really invested time into her students, forming a close bond with us. This allowed for more authentic teaching and for me, I really opened up to how fun, interesting, and diverse science really is.

What are some inspirational materials you’ve used along the way?

Racing Extinction is an incredibly motivating film that I hope opens people’s minds to changing their actions for the preservation of our planet.

Mission Blue, a film documenting Sylvia Earle and all of her incredible accomplishments is also incredibly inspiring.

The most inspiring thing of all is to immerse yourself in nature. When studying the natural world, I’ve found this to be the best way to gain fresh perspective and increase appreciation for what you’re dedicating so much time to.

When I met Sylvia Earle at BLUE Ocean Film Fest in Monaco.

What are some key points you wish you knew or that you remind yourself of during your science career journey?

No matter how groundbreaking or important your scientific findings are, in order to create change for this planet they have to be communicated to a large and varied audience. If there is no communication, the significance of and interest in science decreases.

Also, always keeping in mind and promoting this quote has helped me greatly: “We are not apart from nature, we are a part of nature.” -Prince Ea

What is your big dream?

My big dream is that we will protect and preserve the ocean so that it is as healthy and thriving as possible. The ocean drives our entire planet — getting humans to recognize the ocean’s vitality and make change to effectively protect our waters is my ultimate goal.

Through my career I strive to educate others about that vitality of the ocean, since we can only care about what we understand. Once people understand they will care, and once they care we can work to protect our oceans the way they need to be protected.

Tidepool Guide for Birch Aquarium

~~~

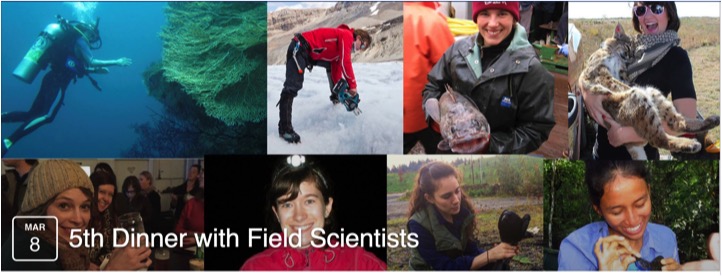

To see more photos of Allison’s adventures, check out the Feature Photo Album on Woman Scientist Facebook Page. Like it and share!

Thank you so much for the interview Allison!

For more on Allison Randolph, visit allisonrandolph.com

To see all of her ocean adventures, learn about marine species, and find ways you can help preserve our planet’s blue lifeblood, follow her on social media @ocean_allison on Instagram, Twitter, & Facebook.

~~~

Want more interviews? We will post interviews with a new feature Woman Scientist every week. In the mean time, you can read from more inspirational women here.

Share this:

by

by

Recent Comments