Her name is Kate Ruck.

An Alaskan friend of mine told me that he had an Alaskan friend who I needed to meet. I love collecting Alaskan friends, so I told him to let her know she’s welcome to come by my house in Seattle anytime!

The day I met her I happened to be throwing a costume party after my 2013 return from Antarctica and I was showing everyone photos on my laptop. After I gave my shpeel I turned around and there was Kate Ruck standing quietly in the door frame. Xtratuf boots and long brown wavy hair framing her big bright eyes.

Instantly I knew who she was and I gave her a huge hug while also feeling completely embarrassed that this Antarctica-Traveling Queen had just listened in on my amateur brag about my travels to The Ice!!

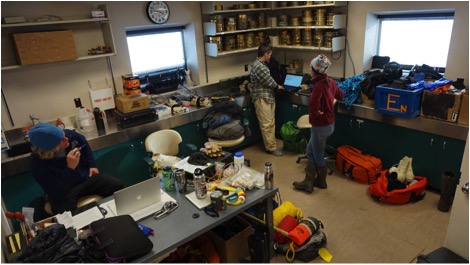

The very evening that I first met Kate Ruck.

Kate travels a lot for work/school.

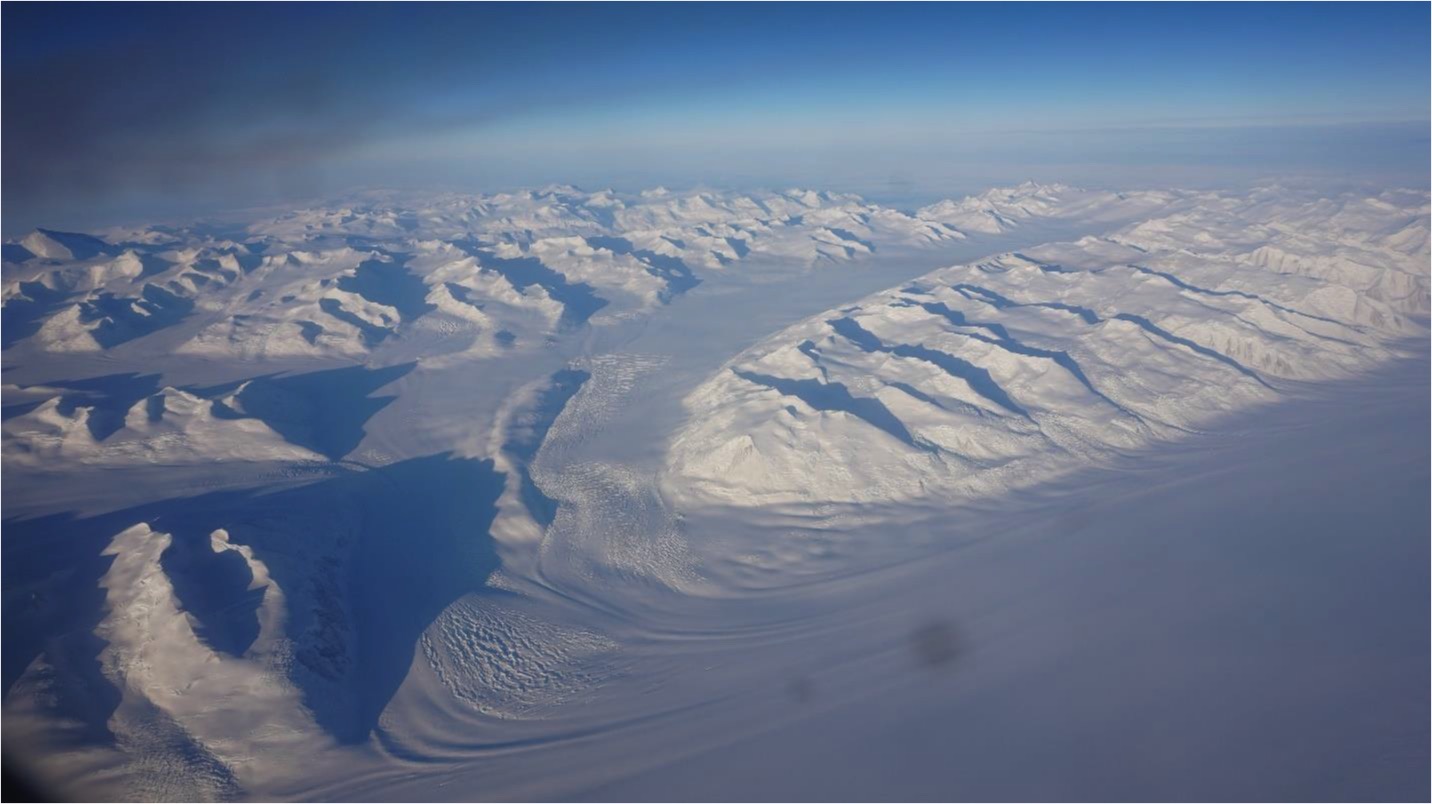

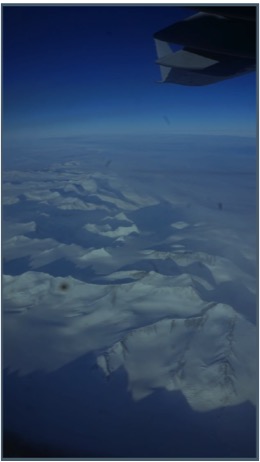

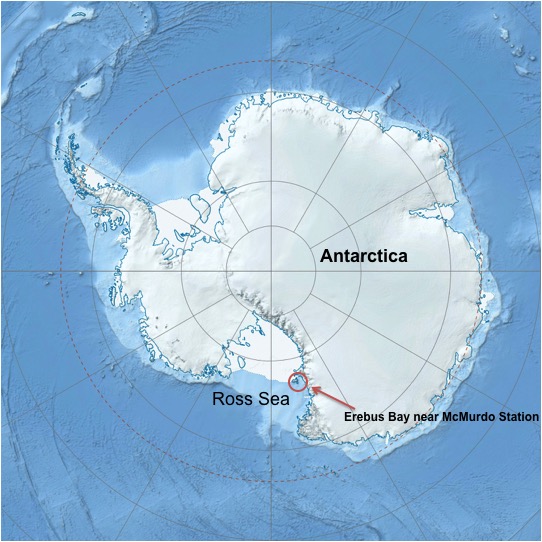

She is gone multiple months out of the year but always returns to Seattle. She was traveling to Antarctica via icebreaker, obtaining her Master’s Degree at Virginia Institute of Marine Science doing work for the Palmer Long-Term Ecological Research (Pal LTER) project and US Antarctic Program.

This work resulted in her first-author publication: Regional differences in quality of krill and fish as prey along the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Kate E. Ruck, Deborah K. Steinberg, Elizabeth A. Canuel.

Every time she is in Seattle we hang out and it’s been a friendship going on strong for two years now.

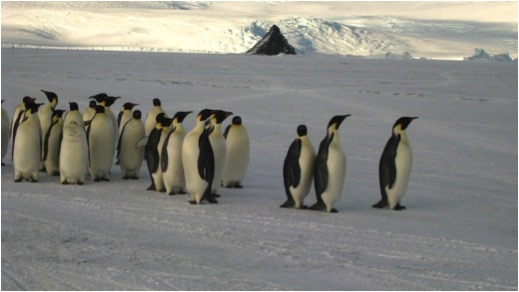

Kate is the definition of badass. She sails with salty sailors, lives out of a suitcase, wields a gun, bosses people around, siences the shit out of everything, hangs out with slimey fish, travels to Antarctica and gets a kick out of animals being dicks. I mean, who doesn’t, right?!

I thought she’d be perfect to interview. For obvious reasons.

Let the interview begin.

- What type of science do you love (if you could categorize the topic e.g., psychology, neurobiology, conservation, wildlife, chemistry, molecular science, physiological, etc.)?

Throughout my career, I have been consistently drawn to Marine Science, more specifically, Biological Oceanography and Fisheries Science. My early experiences in the field were overwhelmingly positive and engaging and I fell in love with all aspects of going out to sea and working on the ocean. Stepping out onto the deck of a boat to have a sea-bound horizon stretching in every direction cultivated an inexplicable sense of home for me and I felt compelled to delve deeper into the science behind my fieldwork. Our oceans are such a large, global resource that are highly utilized and still have not been fully explored or regulated. When I was beginning my career this field seemed ripe with opportunities for meaningful contributions while still providing an outlet to advocate for something that I valued and was passionate about.

- What kind of scientist do you consider yourself?

For the last two years I’ve been making my living as a contract field-biologist, meaning I take short-term seasonal positions working for different research groups as needed. This has been great in terms of travel, experience and getting my feet under me financially, but I am beginning to miss the ability to contribute to the broader impact goals of an established research project. It’s hard to invest two to three months of your life in an assignment you’re passionate about, only to say farewell it when the field season comes to an end. In the broader brush, I’ve lately become very interested in education and outreach. Informing the general public about environmental issues such as climate change, conservation, and our global oceans.

- What is your earliest memory of being hooked by science?

Oddly enough, I remember being captivated by ‘Alba’, the glowing rabbit that was engineered in France by splicing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) of a jellyfish into her genome. It was the early 2000’s, I was just starting high school and thinking about college when genetics and molecular science topics began big in the news. I remember being fascinated by what was possible within the confines of the lab and was delving into books and documentaries on the topic. As I transitioned into college, I moved away from molecular biology because of the political and commercial interests that were starting to invade the field and the amount of competition that was associated with such a rapidly growing and hugely profitable industry. I had always wanted a workplace that was inclusive and highly collaborative. Ecology and marine science seemed like a better fit and my early field experiences got me hooked on the opportunities to be outdoors and immersed in the ecosystems I was studying.

- Who inspired you to go down the path of science?

A long string of incredibly engaging, charismatic, and supportive teachers kept me on the road to a career in science. Listening to lectures and taking labs from people who were so passionate about their profession instilled a love for the natural world that I felt could be the base of a career, rather than a hobby. I also have to give credit to my parents for encouraging me in what I was interested in rather than pushing professions that were less exciting to me but offered a higher degree of job security and financial stability.

- What were some preconceived notions about science or scientists and did that change once you explored your career in it?

I was pleasantly surprised by how relaxed and open I found the professional world of Oceanography could be. I realize that this isn’t everyone’s experience in academia, but my time at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science and my involvement with the Palmer Long-Term Ecological Research (Pal LTER) project was filled with interdisciplinary collaborations, sharing of resources, and a free flow of ideas.

- We can get caught up in the romance of being a “world traveling scientist” but it takes real hard work and a lot of sacrifices to actually do. What were some big compromises or struggles you experienced choosing to go down this path?

While I ultimately love what I do, there are a lot of personal sacrifices that I’ve made by doing this job, the way that I want to do it. Working as a contract field biologist took me away from home for roughly ten months out of the year in 2014. I’ve missed weddings, birthdays, funerals, Thanksgiving, New Year’s celebrations, and the day-to-day companionship of family and friends. Maintaining relationships with significant others is also challenging because there is always a component of long-distance and I am usually working in remote environments where there is no cell phone service or an Internet connection. Starting out, there is also a lack of financial stability and job security. I have seen colleagues leave this profession to pursue careers in the medical or business sectors because the demand and starting salaries are so much higher. Academic science is often operated on shoestring budgets, and when fieldwork is located in an exotic location, it is easy to find well-qualified volunteers or people who are willing to work for travel and living expenses in exchange for the experience. My biggest challenge right now is finding permanent employment with a science platform I respect that is also offering a salary that I feel is commensurate to seven years of experience I’ve accumulated and the two academic degrees that I’ve earned.

- What keeps you motivated when you’re feeling the drudgery? Do you ever hate it? What keeps science fun for you?

Like any job, there have been some awful, overwhelming workweeks that I’ve had to slog through. I have been lucky enough to live and work in some of the most pristine wilderness on the face of the planet, including Antarctica, Prince William Sound, Alaska’s North Slope and the Bering Sea. The other side of the amazing field experiences is that I’ve also logged 40+ hour workweeks for months at a time to organize, prep, and analyze the 1000s of samples we collected in the field; a stationary, monotonous task that still requires a high attention to detail. For me, getting through weeks of long hours or the disappointment associated with failed work is the responsibility associated with ensuring that you’re delivering high quality science to eventually share with the scientific community. I was also lucky enough to have worked in labs where there was a supportive and humorous group of coworkers and graduate students to bring relief to the routine. Opening up and asking for motivation from your peers has helped me through a lot of my unenthusiastic days. Creating and cultivating a supportive work community will bring fresh perspectives and energy to projects that may have become mundane from long hours of myopic familiarity.

- Advice you’d tell youngsters , some key points you wish you knew before you set out.

Surround yourself with people you trust and who are always inspiring you to continue investing in and pushing the limits of your work. Sometimes you may feel compelled to chase an opportunity because it’s the ‘right time’ or the location is ‘too good to be true’, but this work can occasionally require that you invest a lot of your personal time to achieving project goals. Working for and with people who recognize and value the amount of effort you’re contributing will increase your overall satisfaction with the job and ensure that all your effort won’t be taken advantage of. My bosses and peers have been great advocates for me and their connections, support and recommendations have opened up opportunities that I would have never considered within my reach. I also wish that I had done a better job of prioritizing my personal time when I was going through graduate school. When I initially started my thesis project, the amount of work that needed to be done seemed so overwhelming that I would feel guilty when taking time out to do something for myself. In retrospect, making clear definitions between time at work and time at home would have made me more efficient in the lab while making the time to myself at home more fulfilling. Don’t be afraid to carve out those hours to yourself!

Want to see more photos of Kate’s journey? Click here.

Share this:

by

by

Recent Comments