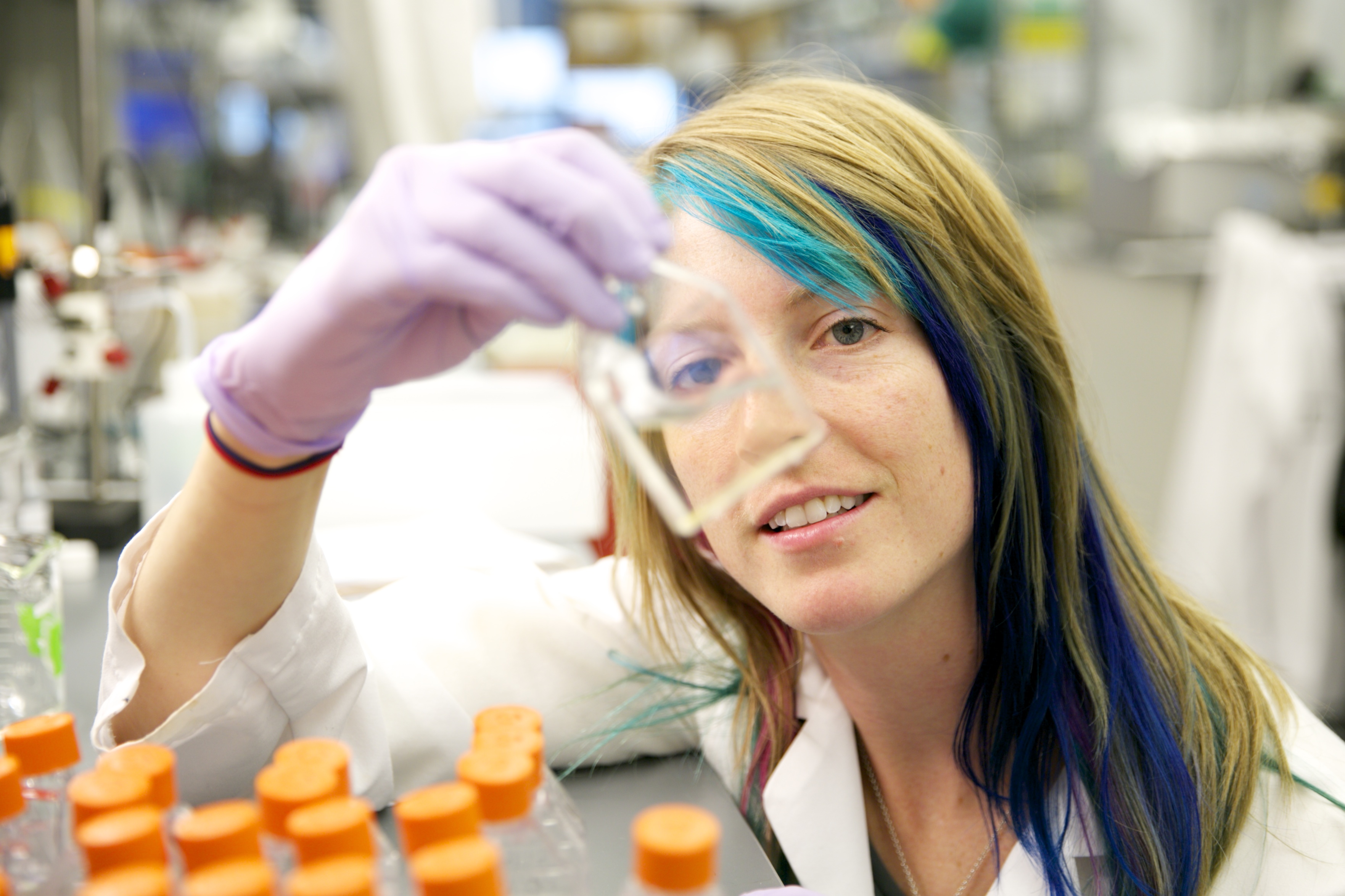

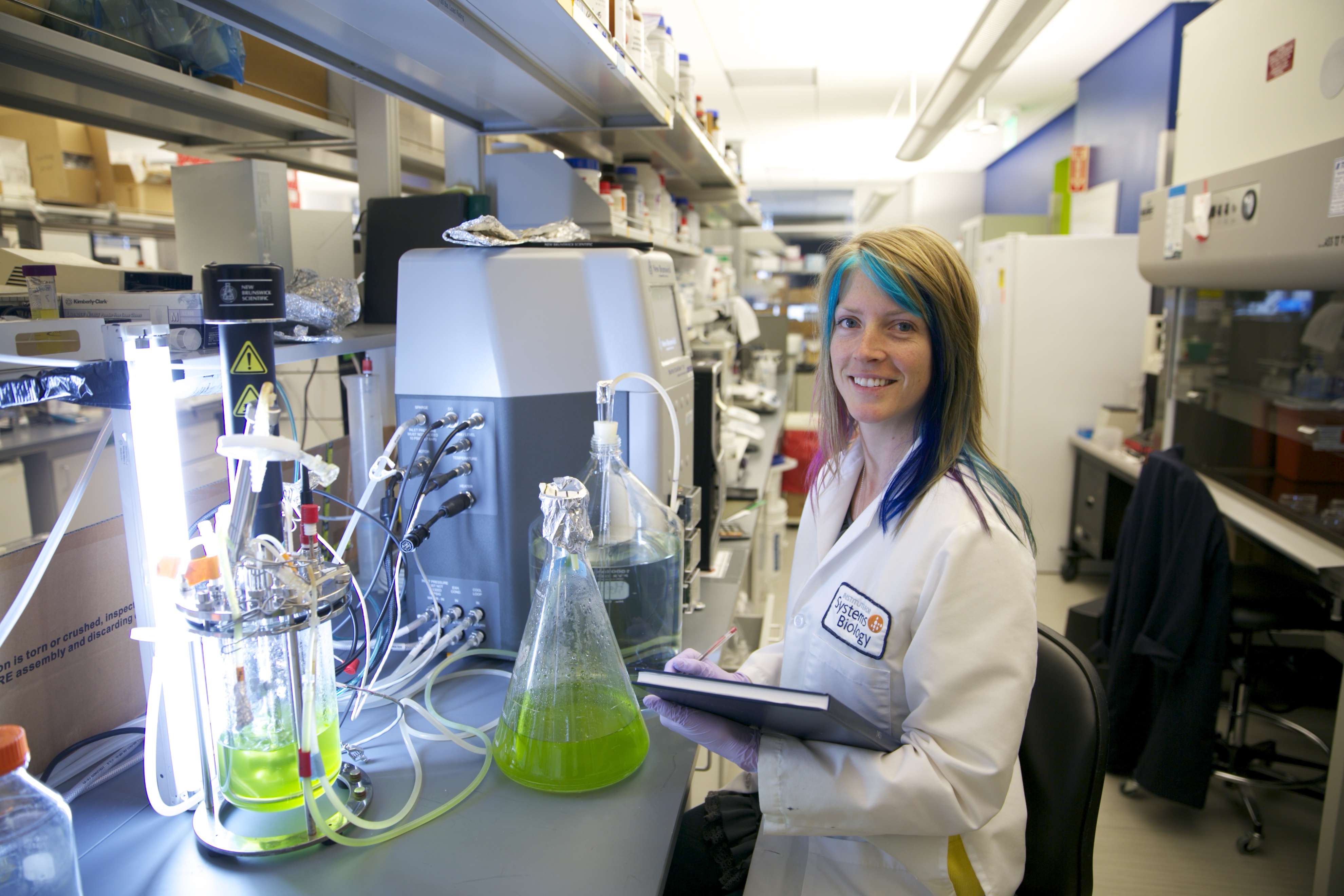

Allison Kudla has an unconventional career: she has mastered a creative solution to work at the interface of three disciplines: biology, art, and technology.

We first met when she joined the Institute for Systems Biology (ISB) as an artist to make our work look as gorgeous visually as it was scientifically. I was amazed with her portfolio, and watched in fascination as she made changes to ISB’s graphic designs. She is certainly a talented artist, and incorporated so much technology and science into her work that she had me confused as to whether she was an engineer or a biologist! I had never imagined a job position like hers before. Naturally, I needed to understand more.

Allison didn’t set off early in her career knowing she would, or even could, blend all three disciplines. She pursued one interest at a time–art being the catalyst–and with each step in the journey more and more was revealed to her. She took on new ideas and new concepts along the way, working them into her ideal framework, and created a space for herself that incorporated her vision for her career. Her journey is not over; She still strives to reach that perfect ideal blend where all of her talents and education can be used. It just goes to show that you can create and accomplish amazing things during your hunt for the elusive career unicorn without getting discouraged that you haven’t yet “arrived”.

Allison’s career creativity is an example we can all follow. I hope you enjoy reading her interview below.

1. Were you first in to art, science or technology? Or were you in to all three at the same time?

I would say art first. In high school I set a goal of creating a portfolio of work that would get me into an art school. Indeed, I was accepted into a few and decided on the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). While there, in my second year, taking a class on Conceptual Painting at the same time as a class on Digital Tools for Painting, I really began questioning why my medium was painting. My concepts were perhaps better conveyed with new media / digital media. From there, I switched to the Art and Technologies Studies program at SAIC and began working with interactive platforms such as: physical computing (sensors and micro-controllers), sound synthesis and graphic programming. I was so excited to be making works that were driven by data taken from the external world. When I finished my BFA, I felt I had only begun this work. After a short time, I was accepted into the first waive of a new practice-based PhD program in the arts at the University of Washington’s newly established Center for Digital Arts and Experimental Media (DXARTS). Here I was challenged again to question my medium, and my knowledge of the systems I use in my work, and there I began exploring the life sciences. This is where biology has its first direct emergence in my artistic work.

2. What led you into art and how did it evolve over time? Did you start out using a certain media and then evolve your preferences from there until you found your niche?

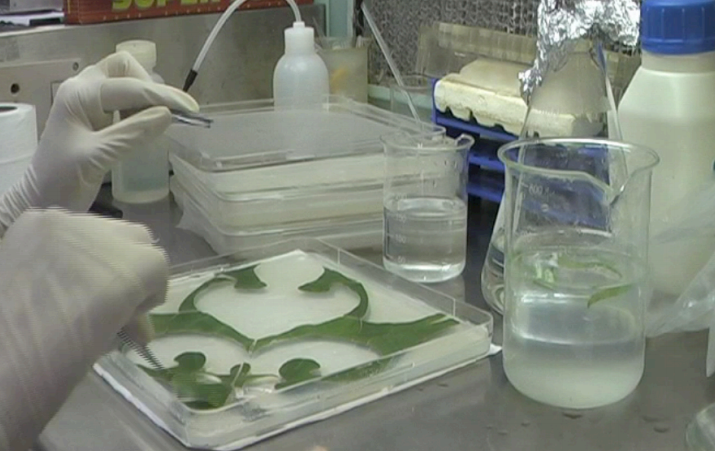

I suppose I am sponge, meaning if it is available to me as a medium, and I am interested in working with it, I soak it in and start using it! It wasn’t until I came to the arts as a graduate student at a research university (UW) that I realized that my medium could involve a greenhouse or a tissue culturing lab just as much as it did a fabrication studio, a machine shop, or a computer lab. I tried to be as imaginative as I could and really think in an interdisciplinary way to solve creative challenges and create visual art.

3. Can you remember your first art project that was at the interface of three disciplines: science, technology, and art?

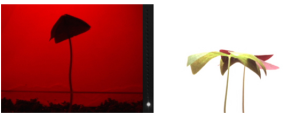

Definitely. It is called “The Search for Luminosity”. It was a system that watched the circadian rhythm of the Oxalis plant and enabled it to control its light source. Oxalis is phototropic and has very broad and large leaves that seem to “open” and “close” when it is attempting photosynthesis. Because the opening and closing gesture is based on a bio-chemical memory of the plant’s previous routine or cycle, even in darkness the plant will lift its leaves. For this reason, I was able to create a robotic system that watched for the plant to lift its leaves, and when it did, it would turn its overhead light on. In short, a poetic framing for reversing the hierarchy of the biological and the physical world, The Search for Luminosity equips the phototropic plant Oxalis with the ability to communicate directly with the acting sun in its universe through the mediation of a technological system.

4. When did you realize, or decide, you could blend all those fields into a successful career? Did you have any idea at first that you’d end up using your artistry in the science world?

I didn’t have an idea. It really happened gradually and in part due to the people around me.

5. Who inspired you to investigate a path involving science and technology? What hooked you onto the sciences and technologies?

Shawn Brixey, my PhD advisor. Check out his work, it is so rad! He asked me a deceptively simple question:

“In art, what is the difference between simulation and emulation?”

This question prompted me to explore what the “operating system” for my work was. I realized that instead of it being Mac OS X drawing a picture to a screen of a representation of a plant or botanical form, I wanted to learn the operating system of the botanical form itself. I wanted to know what algorithms were running on biological systems, and to know this, one has to study biology.

6. Do you have a favorite type of science?

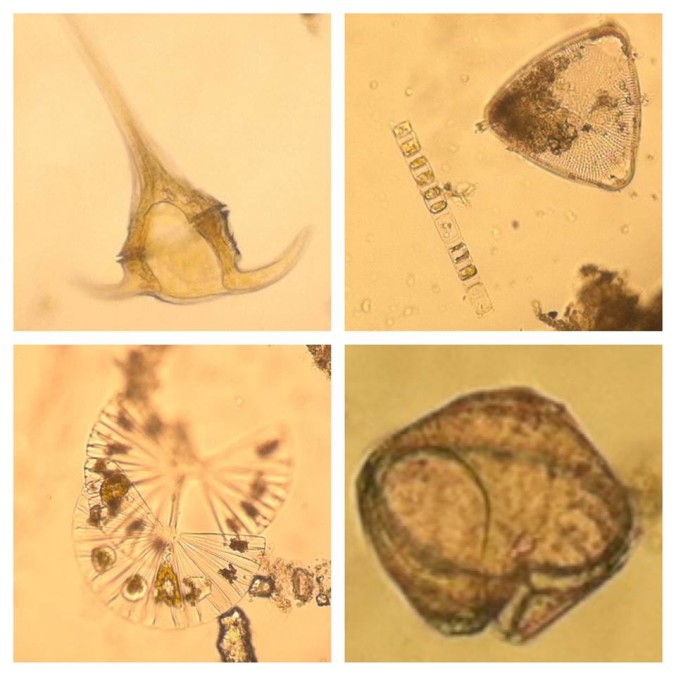

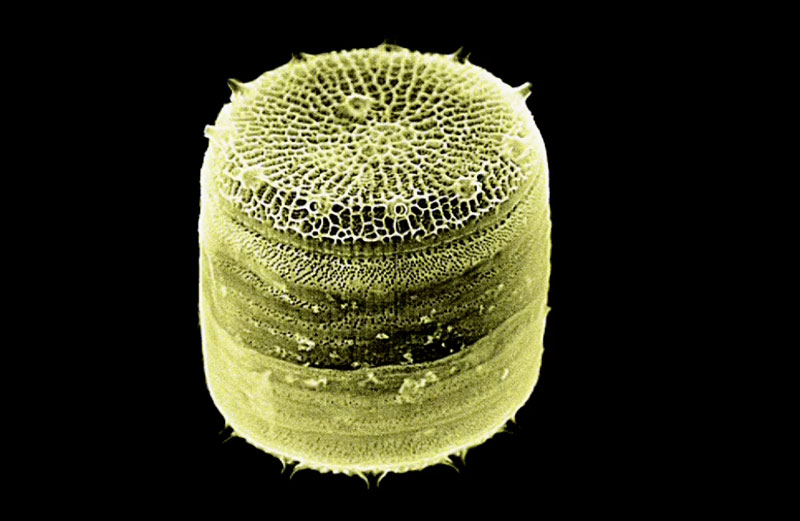

Accessible, breakthrough science that I haven’t heard about before! I am a visual person too, so I really love it when the sciences discover something that can be imaged or visualized in a way that is beautiful. I am really looking forward to seeing data visualizations over the next 10 years and hope to be a part of that work.

I am also fascinated by science that studies how species have evolved to adapt to climate change. I think we can learn a lot from organisms with faster evolutionary cycles and therefore shorter life spans.

Credit: Dr. Allison Kudla, Institute for Systems Biology, illustration featured on U.S. NIH website for The Cancer Genome Atlas Project.

7. What were some preconceived notions about art, artists, science or scientists and did that change once you explored your career in it?

I think when I was younger, I thought scientists were not imaginative. I really don’t know why I thought that because the more scientists I interact with, the harder it can be to tell them apart from artists. 🙂

8. What were some big compromises or struggles you experienced making a career out of this? Did you have any roadblocks (mental, emotional, physical) or did you feel supported along the way?

This is a really hard question. I have had a lot of support and interest, but I have also faced some serious challenges. If you think science is under funded in America, check out art! And if your art is living and temporal, something to be “experienced” but not necessarily bought and sold, then it can be even harder!! I still wonder if I will ever have a salaried job that takes advantage of every aspect of my education. At the same time, I think it is my responsibility to blaze this trail for others like myself — and it will take decades, likely. There are so many art residencies, but these opportunities force artists into being nomadic — moving from place to place every four months or year without knowing what the next year or two will look like or where they will be. This adds to the stress and struggle, and also can severely limit an artist’s ability to work on projects that are longer term, or involving science and technology. As you’ve heard before “science is slow” and so is art + science research.

9. What keeps you motivated when you’re feeling the drudgery? Do you ever hate it? What keeps it fun for you?

Any long process that involves precision, technique, conceptual robustness and creativity is going to involve drudgery. I think I hate it most when I am not sure if it will be a success, or I try to explain it to someone else and I don’t see any sparkle in their eye. Then I have to just hope it was a failure in my words and they will get it when they experience the work.

Working with other people keeps it fun. Being in a feedback loop with the finished product keeps it fun. Having a plan as to where it will be presented also keeps it fun.

10. Who are some personally inspirational people in this field?

There are so many. First three that I hadn’t already mentioned: Natalie Jeremijenko, Daisy Ginsberg, and Paul Vanouse.

11. What are some key points of advice you wish you knew before you set out?

Geometry is incredibly important in art and visualization. And in general Math is a universal language and key to understanding operating systems in biology, computation and technology. It’s okay if you forget formulas because the internet can help you. However, understanding the concepts are essential for success. If something isn’t making sense in class, talk to your peers and mentors. There may be other angles you need to see some of these concepts from in order to understand them better.

Fast Facts

- Exhibitions & Publications

- BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

- Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore, India.

- PhD from the University of Washington’s Center for Digital Arts and Experimental Media (DXARTS)

- Communications Designer at the Institute for Systems Biology.

- Her full work can be viewed at here.

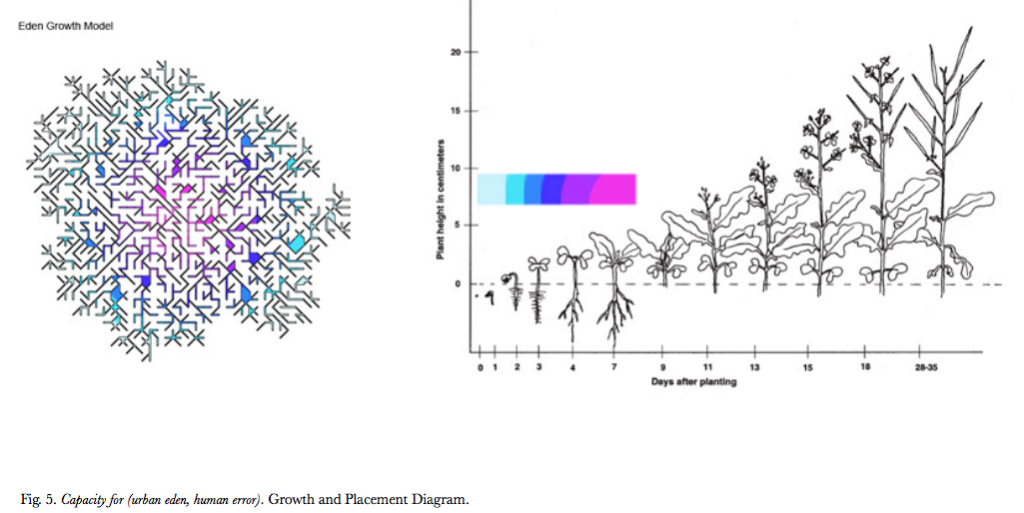

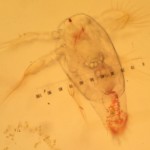

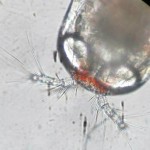

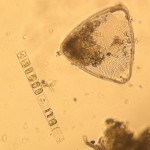

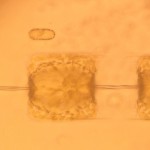

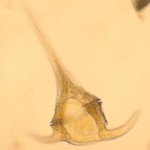

- All Figures were taken from her dissertation which you can read in full, here.

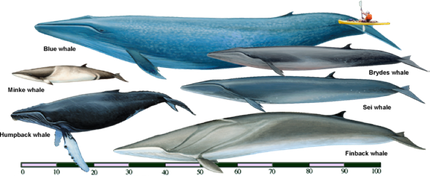

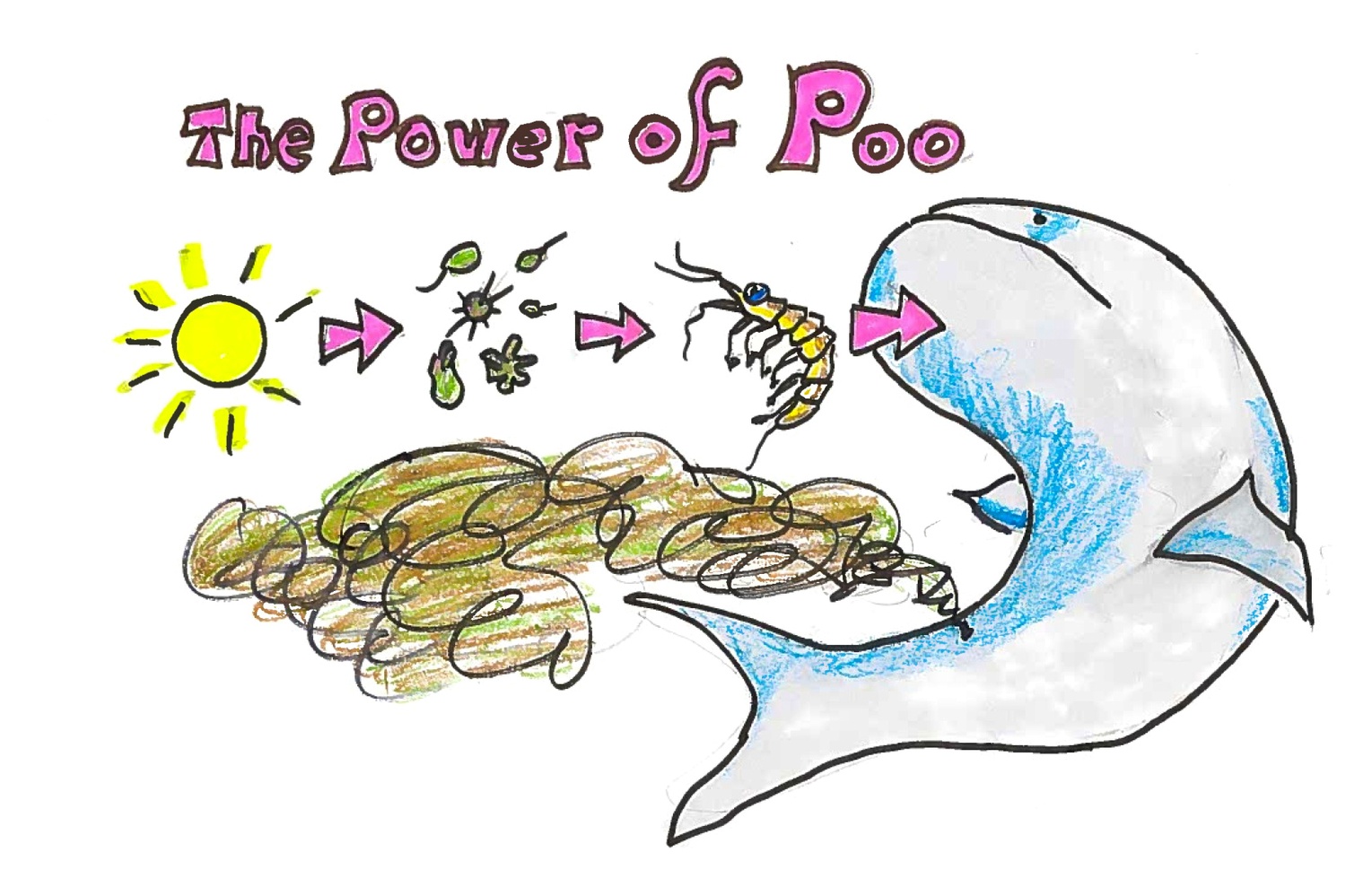

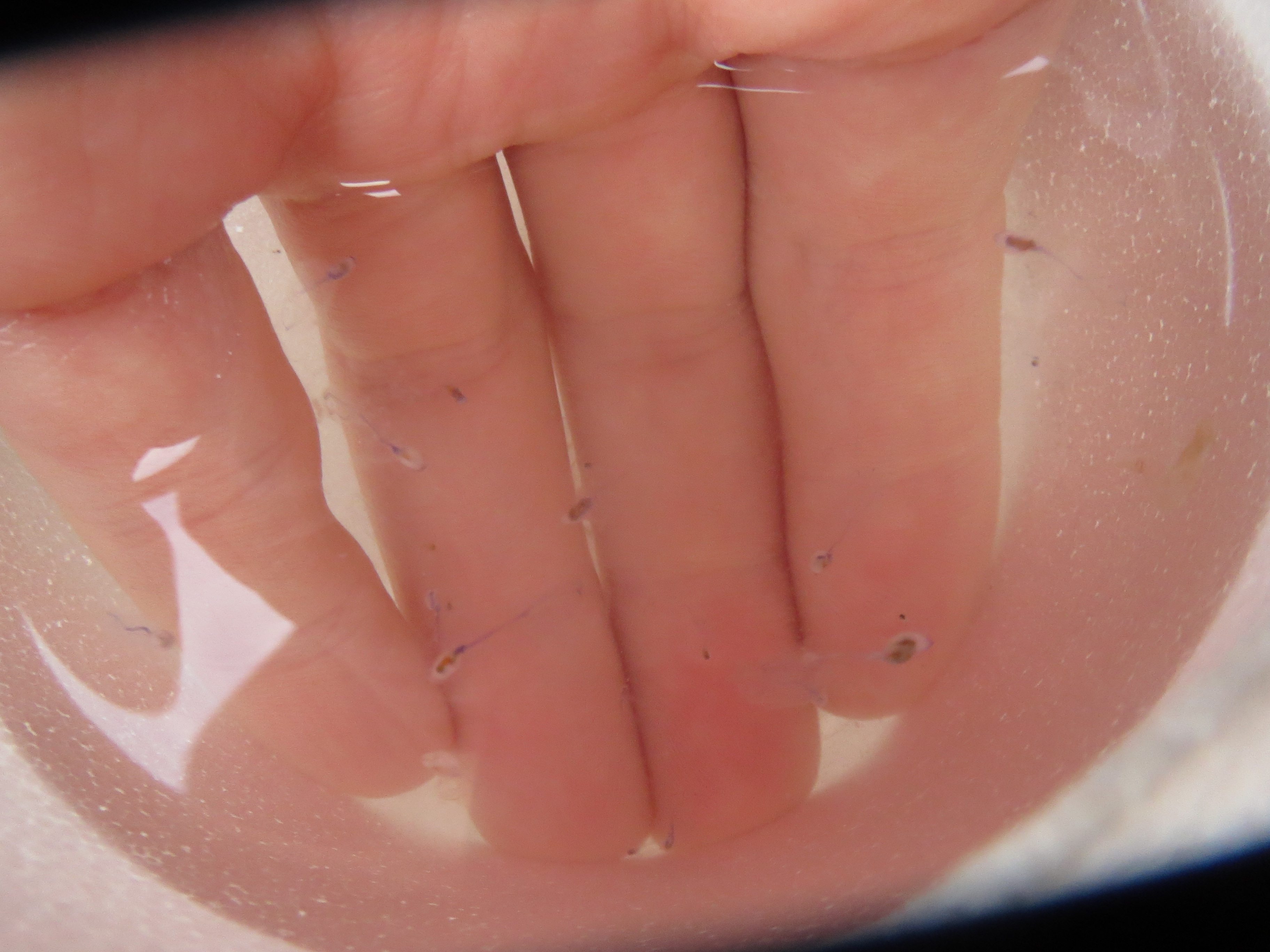

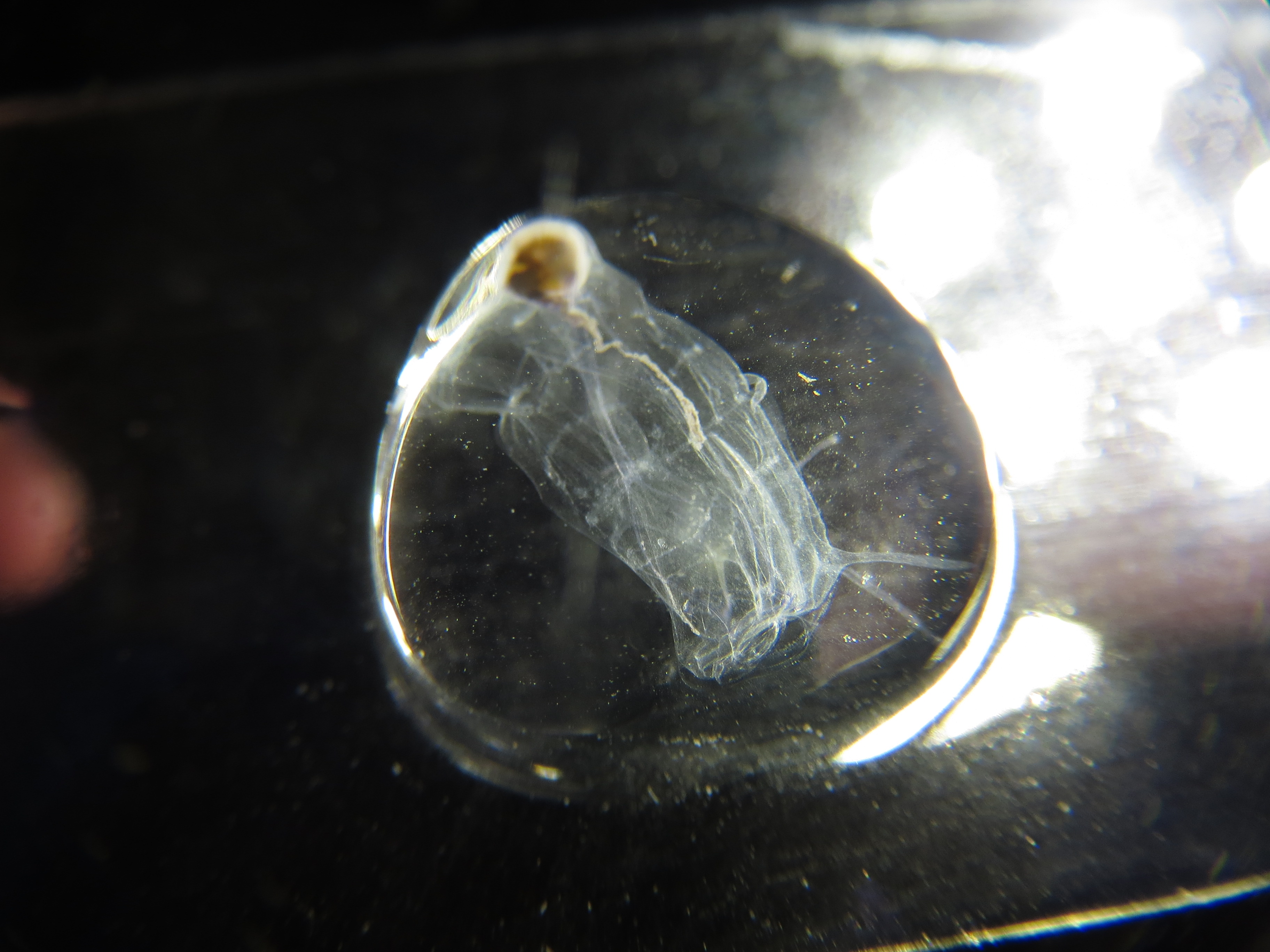

Magnificent Blue Whale pigmentation and the mouth of a Humpack Whale.

Magnificent Blue Whale pigmentation and the mouth of a Humpack Whale.

Recent Comments