How do I even begin to tell all of the stories from 4.5 weeks observing Big Cats in Kruger National Park, South Africa?! I came back with over 68 GB of photos, videos and a mind full of memories.

Do I first tell you about the time we watched a young male leopard attempt to kill a ground hornbill and fail?

Watch the video of that surprise attack here.

Do I tell you about the white lion cub we saw fighting its brothers in the pride for a piece of freshly killed zebra?

Do I tell you about the day we followed a wild dog pack and got caught in the middle of their napping session, or about the evening we sat on the top of a hyena den watching baby hyenas explore close to their sleeping parents?

What about the morning a lioness disappeared behind a rock outcrop only to reappear with a tiny cub in her mouth.

Do I tell you about how funny long-necked giraffes look when they bend down to get a sip of water or about the absurdity of a leopard attempting to kill three porcupines stuck in a drainage tube?

How about the five bull elephants we sat ten meters from, or the bush walk we took with park rangers that brought us twenty-five meters from white rhinoceros?

I could go on! Do you see my predicament in recounting everything? I wish I could go back there and take you with me.

100% of the time that my eyes were open during that month, I reflected on how amazing it was to be able to wake up with every morning sunrise, see all of these wild animals up close and personal, camp under the starry skies, and come away with so much knowledge of African wildlife.

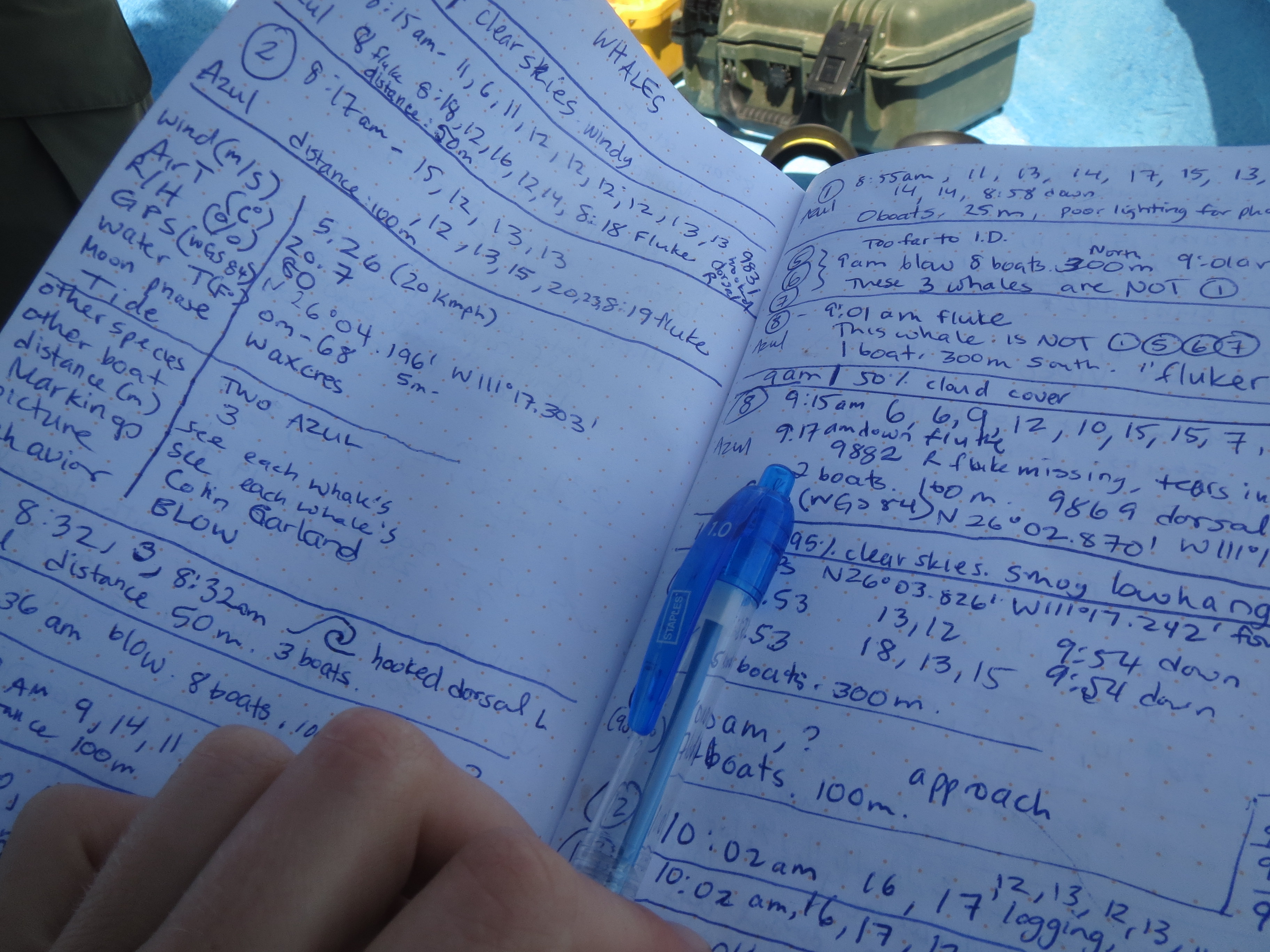

Every animal encounter triggered a rapid fire photo shoot followed by awe-filled observations and furious journal entry writing. This could last for hours and you never wanted to be caught on a lion kill with a full bladder!

So who were we and what were we doing down there?

We spent a full month in Kruger National Park observing the behavior of the three big cats: lion, leopard, and cheetah. Students gained hands-on experience in observational field work, animal behavior research, and conservation photography/videography.

As far as amazing educational african wildlife adventures go, the price of this trip was extremely reasonable. For a 2-week trip, participants paid $3,995 which included airfare from JFK, food, lodging, tents, and transport. There was an additional Kruger Park conservation fee of $290 and additional guided night drives or bush walks were $45 and $65, respectively. Every penny was worth this access to Nature’s african gems.

During the month of June, two groups experienced camping in the park:

Kruger National Park is one of the largest game reserves on the entire african continent and was established in 1926. Comparable to the size of Israel at 7,523 mi², it looks dwarfed compared to the entire country of South Africa.

For each 10-day trip, we only managed to cover the lower portion of the reserve. Every two to three nights, we would relocate camps beginning the trip at camp Berg-en-Dal, moving on to Lower Sabie, then Skukuza, Satara and finally, Pretorioskop.

Our days were spent from 6:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. sitting in an awesome Volkswagon Synchro van driving around the dusty bumpy dirt roads scanning the tall grasses, thorn-veld, or savannah for any clues of big cats.

Cars have been coming to the park for 100 years and because humans have never hunted the animals from vehicles, the animals have become habituated to the engine noise and vehicle presence. This allows tourists to get remarkably close and the animals who don’t seem to mind (until the humans start talking too loudly). Some predators have even learned to use the cars as shields in their hunting schemes.

A couple of times during the month we took morning bush walks. I was expecting every animal to be out to get us and was very surprised to witness that once we got on foot we became the top predators and every species that caught our scent fled: elephants, giraffes, rhinos, even a pack of lions! Because humans have been hunting these animals for over 2 million years, they are all very aware of the danger our recognizable human form poses.

The Nature of the Park

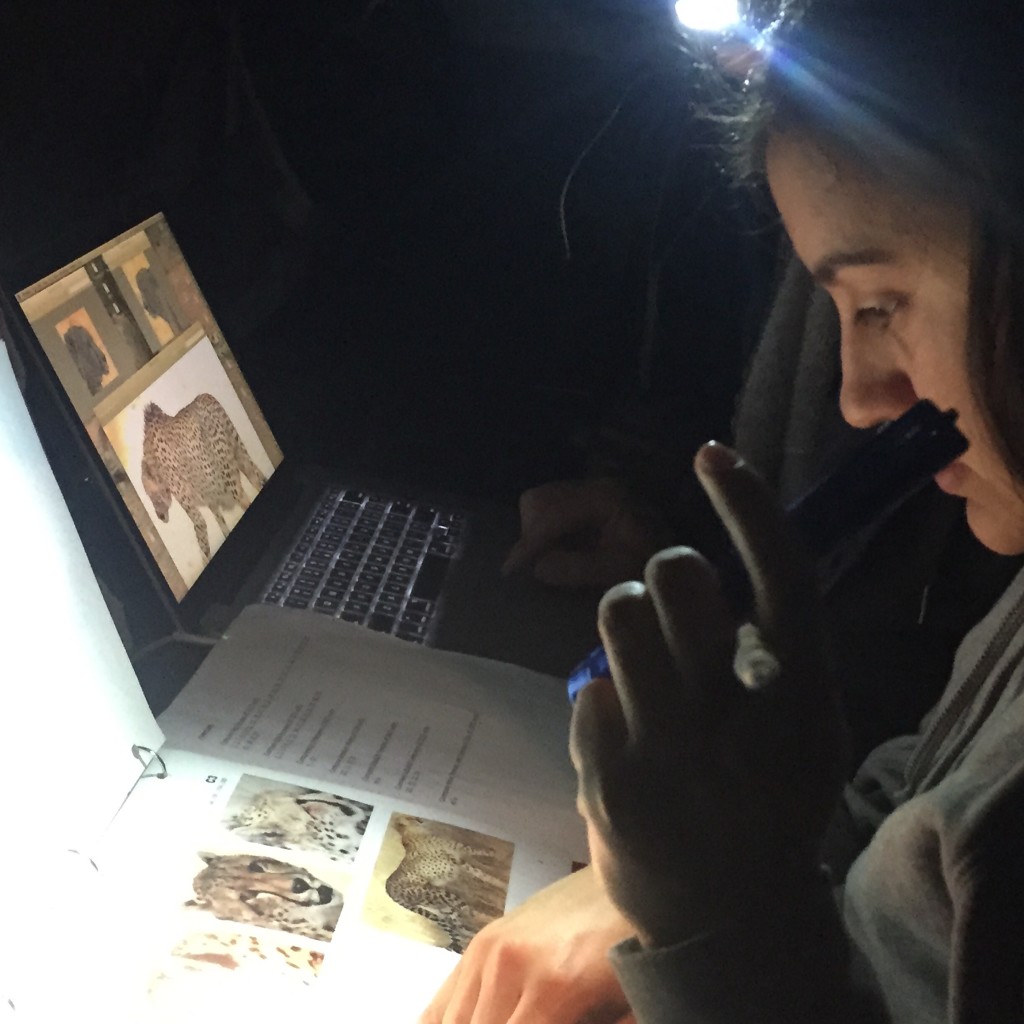

When I arrived, the first thing I did was gobble up all the knowledge I could about the park: the geological history, the vegetation and landscapes, the animals. Acting as co-leader for the month, I personally took on a set of responsibilities and had a lot to learn before the students showed up! I used old guide books from the park to give myself a crash course of the area.

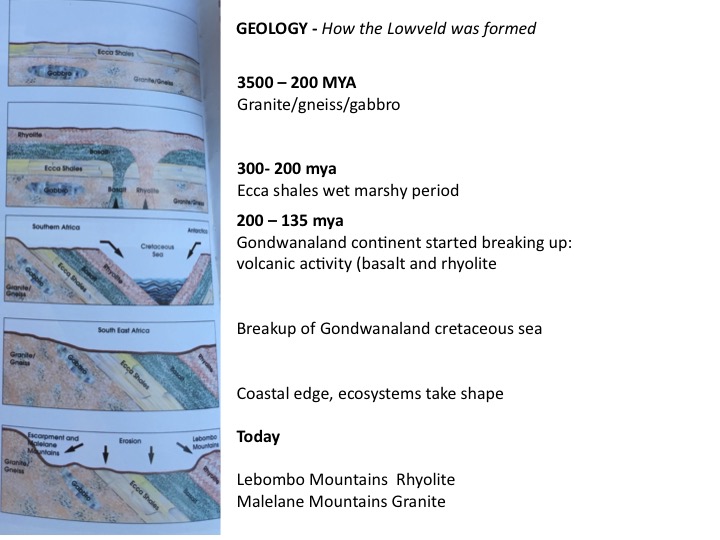

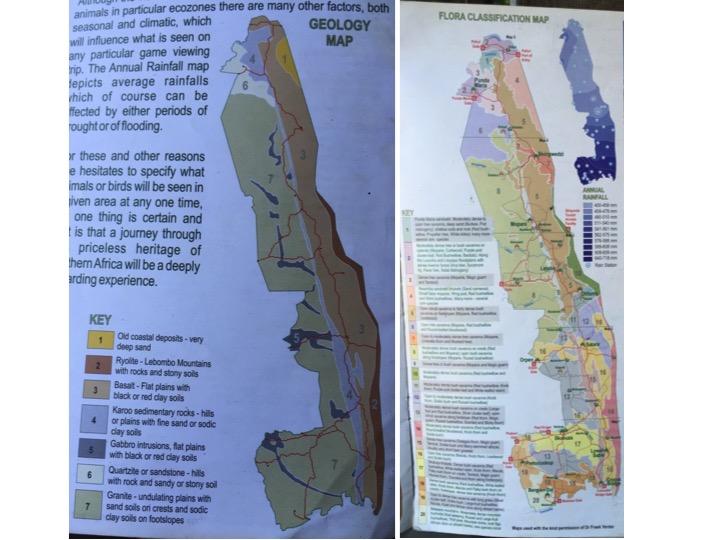

One of the most important aspects of the park is actually it’s diverse geological makeup. The park’s main living attractions are dictated by the entire geology hidden under the vegetation.

It started long long ago, when the super continent Gondwanaland still existed, before Antarctica split off from Africa. Layers and layers of rock types were laid down through earth’s dynamic tectonic activities. As Gondwanaland broke apart, ancient rock was exposed and slowly eroded over time leaving the area as we know it today:

Due to the various type of rock and soil exposed at the surface, there is an incredible diversity of flora in this tiny slice of land. This creates unique eco-zones which dictate where you’ll most likely find certain species of animal.

Meet the Herbivores

Just like you have your favorite food preferences, so do the herbivores. Different grasses and bushes attract different types of herbivores. Impala are the chicken nugget of the park, abundant every where you turn. Others such as Kudu, Waterbuck, Cape buffalo and Wildebeest roam about following their flora of choice. I expected these prey animals to be more timid than they were but the zebra were the only species on a whole that were the most skittish.

Waterbuck have distinct bulls-eye rings on their behinds. When they get stressed they release a nasty tasting hormone which deters predators from attacking.

A Typical Day

We woke at 4:45 a.m. every morning to be first to the gates. At 5:15 a.m. my alarm clock would go off and I would debate hitting snooze for two more minutes before finally getting out of the tent and making the wake-up call to the others.

With sleepy eyes, we brushed our teeth and put on our warm layers–hats and gloves–as some mornings were a chilly 47F. At 6:00 a.m. sharp, the ranger would open the doors and we’d be on our way spotlighting the road-side looking for lingering nocturnal animals.

My favorite time of day was sunrise. It always felt like you had a secret the rest of the world wasn’t yet in on.

There was never a day we went without and animal sighting. When we did find the animals, it became a photographers dream. Click click click. We’d shoot and swap lenses and duck under and above each other to get the best look at the animals.

Some days we had permits to get out of the van and investigate old bleached bones on the ground. One day we found this elephant skull and it became an excellent education opportunity to learn how one can build a story of a particular elephant’s life by looking at distinct features on the skull.

We also paid attention to how to read tracks. Through close observation one could tell the mood and direction the animal was traveling. He talked about identifying the age of the track based on erosion patterns. Below you can see the footprints of hyena, jackal and a large bird (perhaps a korhaan).

Through patient observations, we gained vast knowledge of animal behavior.

One day we spent at least three hours watching a family of hippos eat, sleep, procreate, and play in an algae covered pond. This baby hippo (pictured below) crawled out of the lagoon and actually fell asleep near this crocodile! Hippos seem to have a great understanding of respectful cohabitation, but eventually this hippo’s mom came and chased the croc back into the water.

Two types of rhino exist in the park: the white rhino (or wide-lipped) and the critically endangered black rhino (or hook-lipped). White rhinos are grazers and use their square lip to graze the grasslands. Black rhino, are browsers and use their hooked lip to browse each leaf off of thorny bushes.

Our bush-walk ranger, Matwell, explains the size and impact of the bullets used in his protection gun.

Sadly, we saw three poached rhino bodies. Poaching is still a huge problem in the park, as I suppose there is much corruption around the issue.

We got rumor that in April alone, 28 rhinos had been poached. Kruger National Park is the most prominent target for poachers and if you want to know more about the ivory trade National Geographic did an excellent article you have to read.

Between January 2014 and 6 August 2014, the Department of Environmental Affairs announced that out of the 631 rhinos that had been killed by poachers, a shocking 408 were killed in Kruger.

Unexpected delights

I did not realize how adorable hyenas would be. Mainstream movies make them out to be vicious scavengers but it turns out they hunt 90% of what they eat and lions are more scavenger than hyenas!

We found two drainage ditches in the road that had denning families which allowed us to literally be on top of their home. Their big eyes, big ears and curious faces made them seem like they could be cuddly stuffed toys.

Baby hyenas. Only a couple weeks old  Sight seeing sometimes got pretty tiring. This is how most of the students spent their day:

Sight seeing sometimes got pretty tiring. This is how most of the students spent their day:

Blackmail! Just kidding, this was actually the day we picked them up from the airport so they were jet – lagged and sleeping on the five hour drive from Johannesburg to Kruger.

Even if some days held sparse animal sightings, we always managed to behold other goodies like this giant millipede.

Bird watching was also plentiful: Lilac-breasted roller, Cape starling, Goliath king fisher, Crested barbet, Walberg’s eagle (white morph), Saddle-billed stork, Ostrich, Lappet-faced vulture, Helmeted guinea fowl, Southern yellow bill hornbill.

My all time favorite: the critically endangered, cross between what looks like a turkey and a toucan, the largest of the hornbills: Ground hornbill. Check out those eyelashes!!

And of course, there were the Big Cats

What Happens When We See the Big Cats?

In total for the month of June we had 101 lion sightings, 33 leopard sightings and 7 cheetah sightings.

The Day Comes to a Close:

Inevitably, the sunset would come earlier than we wanted and we’d catch ourselves racing back to the camp in time for the electric gates to close for the night.

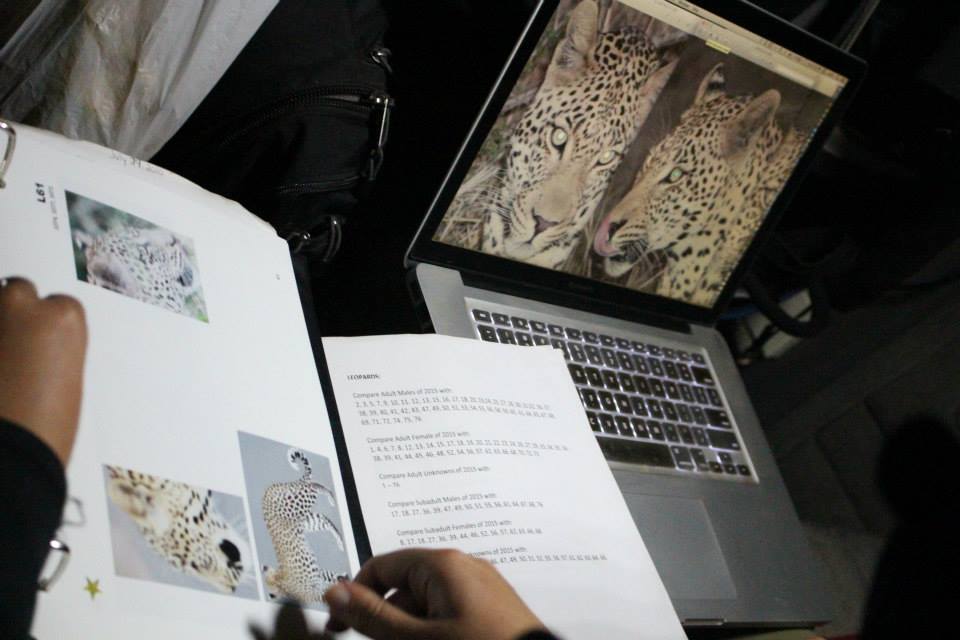

Photo Identify the big cats we saw and either match them up with the catalogue or enter in new individuals!

We also each took turns blogging every night. Writing a narrative gave the day’s data sheets context and flavor!

Each day was full but they all seemed to end too early. Everyone was in bed around 8:30 p.m. and rarely did we stay up past 11 p.m. We were rocked to sleep by the chirp of cicadas, the roars of lions in the distance, of hippos grunting their disputes, and of bush babies screaming their all too human-like cries.

This was a grounding and unforgettable experience. Each group bonded in their own unique ways. Colin did a great job passing on his vast knowledge, mentoring us in the ways of the wild, and I am grateful to also have had the opportunity to play a mentoring role to the young adults as well.

We were all definitely spoiled with the gems of African wildlife.

I would go back in a heartbeat.

If you would like to see more photos from the trip, visit the photo album here.

Share this:

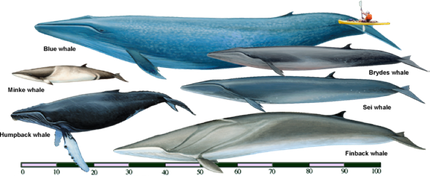

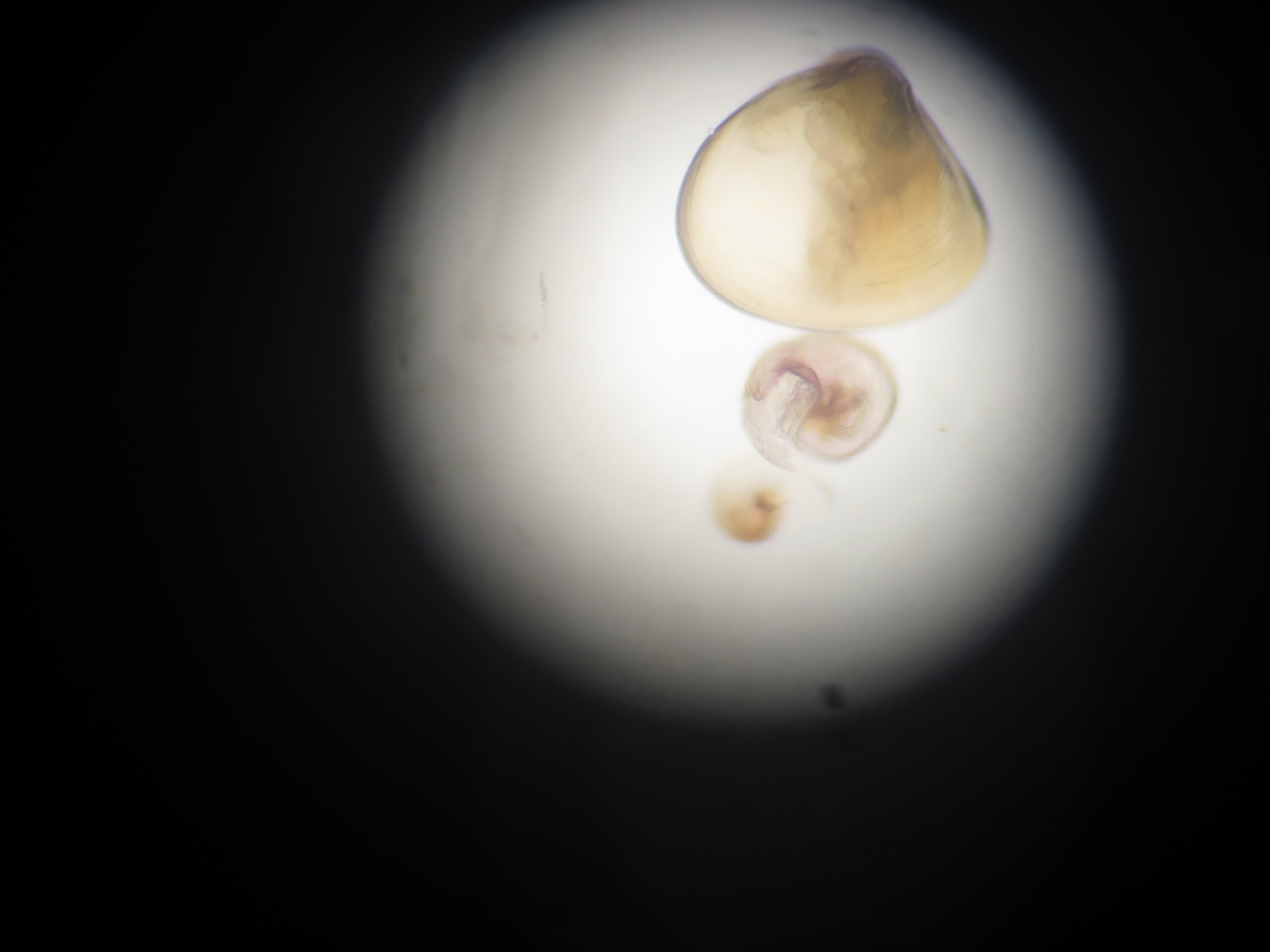

Magnificent Blue Whale pigmentation and the mouth of a Humpack Whale.

Magnificent Blue Whale pigmentation and the mouth of a Humpack Whale.

Recent Comments