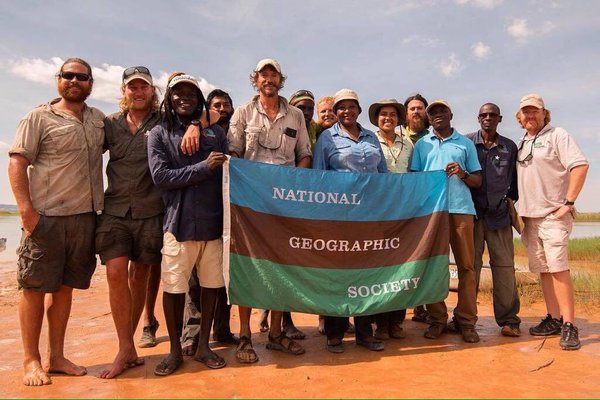

The dream started when I attended a National Geographic Live! event at Benaroya Hall in Seattle, WA on November 2, 2015. South African conservationist, Steve Boyes, and Multi-disciplinary artist, Jer Thorp, led a “live-data” expedition across Botswana’s Okavango Delta in 2014 and presented the results with Seattle.

The team of baYei River Bushmen, scientists, artists, writers, photographers, bloggers, naturalists and engineers traveled from the Okavango Delta river source waters in Angola all the way through to Botswana documenting the numerous biodiversity they encountered, sharing it in real-time with thousands of followers. They recounted tales of discovery and danger, captivating the audience and stirring my wanderlust.

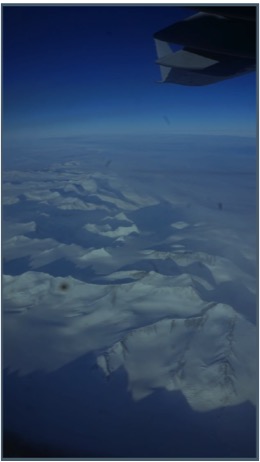

Photo Credit: National Geographic team

Fast forward a couple of months: January 7, 2016. A friend, Kirsten Gardner, tipped me off to a fundraising event to help raise money for Dr. Gregory Rasmussen’s Painted Dog Research Trust in Zimbabwe. “It could be a good networking opportunity,” she said. Boy, was that a foreshadow for what was to come.

I had never been to a true auction before, much less bid on anything. And with the entry price being $50, and me being a non-profit scientist, I told myself I would bid on nothing, I was only there to network.

As nervous as I was, knowing no one in the room personally, I encouraged myself to sit down at the table in the front where sat the Woodland Park Zoo’s Vice President of Field Conservation, Fred Koontz, Dr. Lisa Dabek, a National Geographic Society/Waitt Grants Program grantee and founder and director of Tree Kangaroo Conservation Program, and wire artist Colleen with Colleen R. Cotey Studios.

The auction got started. I listened, intrigued as small items racked up high bids. Then, the bigger items came. Weekend get-away adventures, wine packages, large wire sculptures.

I held fast. Nothing really interested me enough to actually make a bid. Then, the auctioneer said it. The magic words: All-inclusive 7-day trip to the Okavango Delta.

Whaaaaaaat?! The Okavango Delta? Holy crap. Seriously?? I had dreamed about going there the day I heard the Nat Geo explorers talk about it in November!

Ultimate Africa has donated an all-inclusive 6 night / 7 day Botswana and Victoria Falls safari for 2 people valued at US $20,000. Two nights at their Savuti camp, followed by three nights at Vumbura Plains all ending at Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe. Puddle jumper flights and ground transportation needs from Maun to Victoria Falls were included.

Photo credit: wilderness-safaris-vumbura

Photo credit: Allison Lee wilderness-safaris-savuti

Typically I don’t travel in luxury. I’m more of the camping/getting dirty/on-the-cheap/roughing it type of gal. But this. This, I had to bid on.

The bid started low: “Going for $1250, we have $1250, anyone for $1250, next at $2000, $2000, anyone for $2500? We have $2500, anyone for $3000, $3500?….”

The bid crawled up to $5500. I quickly did the math for two: wait a minute, that’s only $2750 per person! I had to act fast.

I held my card in the air: ME!

“$6000?”…

Another guy took the bid. Dammit!

The price climbed… $7000? … $7500?

Trip for two. Six nights. Okavango Delta. All inclusive. High end (glamping) luxury safari. Got it. I knew that last year I had spent a month in Africa for $4000 so I set my price point and told myself I wouldn’t go over that per person.

“$8000, do I hear $8000?” Prices were climbing fast.

Fuck it.

ME! I held my card high again.

“$8000, anyone for $8500? $8500? Going once? Going twice? $8000 to the young lady!”

Oh. My. God. What have a I just done?? I felt slight shock.

Everyone congratulated me and I held a smile on my face. Luckily, I had just paid off my credit card 10 days earlier, so there was room to go right back up to my credit limit. (Despite this story, I’m actually very good with money and have an above 820 top credit score. What’s money good for if you don’t spend it, right?!) Plus, it was going to a good cause. I already know adventure and conservation are my weaknesses financially.

Dr. Rasmussen approached me to thank me and I quickly told him I was also a scientist if he wanted help in the field. “Could I stay on after my trip and come visit you in Zimbabwe?!” I begged.

“Absolutely!” he exclaimed. “But only if you like picking up poop.” (A comment only true wildlife biologists would get giddy over).

Phew. OK. My $8000 7-day trip for two would now become a month long trip for me. I would spend the safari in Botswana with someone (didn’t know who yet), then we would pop over to Zimbabwe to hang out with Dr. Rasmussen. I could handle that.

I sped home and furiously began to text anyone I knew if they wanted to join me on this adventure. I spent all night in a panic hearing “no” after “no” after “I would love to but can’t afford it”.

Then, I found her.

The lucky Partner in Adventure: my mom.

It was during the next couple of month’s that I found out I would be leaving my job at the Institute for Systems Biology to attend graduate school in June at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. I debated selling the trip since I would no longer have a salary, but I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. I HAD to go. Africa was waiting.

We booked our trip for December 10, 2016 (during my school’s winter break), and planned for it to have three parts:

- Cape Town Road Trip in South Africa

- Okavango Delta Safari in Botswana

- Visit with Dr. Rasmussen and Painted Dog Research Trust in Zimbabwe

My mom would spend 15 days total in Africa, and I would stay for 24. Then, we waited patiently for the day to arrive.

Ultimately, the trip ended up being pretty costly after purchasing flights from US to Africa, and flights within the countries of Africa ($3100+ in flights and travel insurance). But it was all worth it in the end.

I’ll end the story here in this blog post as its getting very long.

Stay tuned for continuing stories of Okavango Delta, Botswana and Zimbabwe Adventures…coming soon!

To see the next post on Part 1 of the Okavango Delta, click here.

For those interested in what my packing list looked like, here is the run down with comments on what I used and wished I had packed.

- sandals (luna)

- flat walking shoes (Toms)

- Running shoes (didn’t really wear)

- warm socks (only wore one pair once)

- bra (2 sports)/undies (10)

- water bottle (used a lot)

- cards (didn’t use)

- book (read 2: Half-Earth by EO Wilson and Citizen Scientist by Mary Ellen Hannibal)

- ziplocks

- bug spray

- small first aid kit

- toiletries (toothbrush, toothpaste, shampoo, dry shampoo, floss, glasses, contacts, moist wipes, kleenex, chapstick, sunscreen)

- sunglasses

- good binoculars

- pretty scarf (dresses up any boring outfit)

- gloves/hat (didn’t use, but if I traveled in their winter, might have needed)

- allergy meds/ibuprofen/malaria pills (used! Don’t forget the malaria pills)

- headlamp/batteries

- down jacket (only used on frigid airplane)

- zip up hoodie sweater (used to ward off mosquitos but was too heavy for heat in general)

- african print sweatshirt (great! light weight but gave good coverage and comfort)

- two light weight hiking pants

- one pair of shorts with pockets

- three light t-shirts (blue, black, and blue)

- two tank tops (black and white)

- Safari button down long sleeve shirt (loose fitting clothes are excellent)

- poncho (used once in a downpour)

- GoPro / cords

- iphone / cords

- 6-charge battery pack (VERY handy)

- small foldable backpack (day bag also used as additional carry on item for books and airplane needs under my seat)

- small coin/card purse (could fit passport and phone)

- small notebook/paper/pen

- quick dry towel (never used)

- 26 Clif Bars, just in case food situation wasn’t good (only ate 4, gave the rest away)

- one 44 liter/2650 cubic inch carry on backpack to fit it all in (mine is the very old version of Kelty Redwing 2650)

*Featured Image photo credit: Allison Lee

Share this:

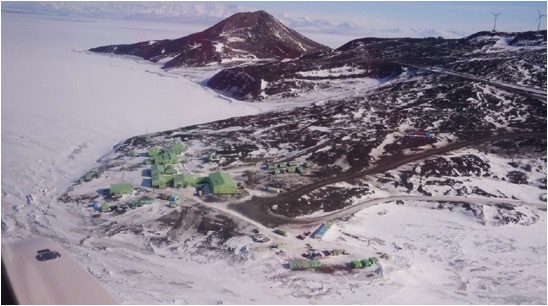

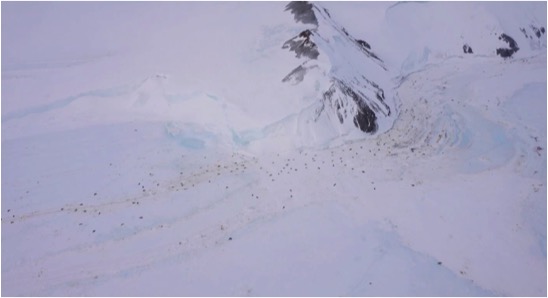

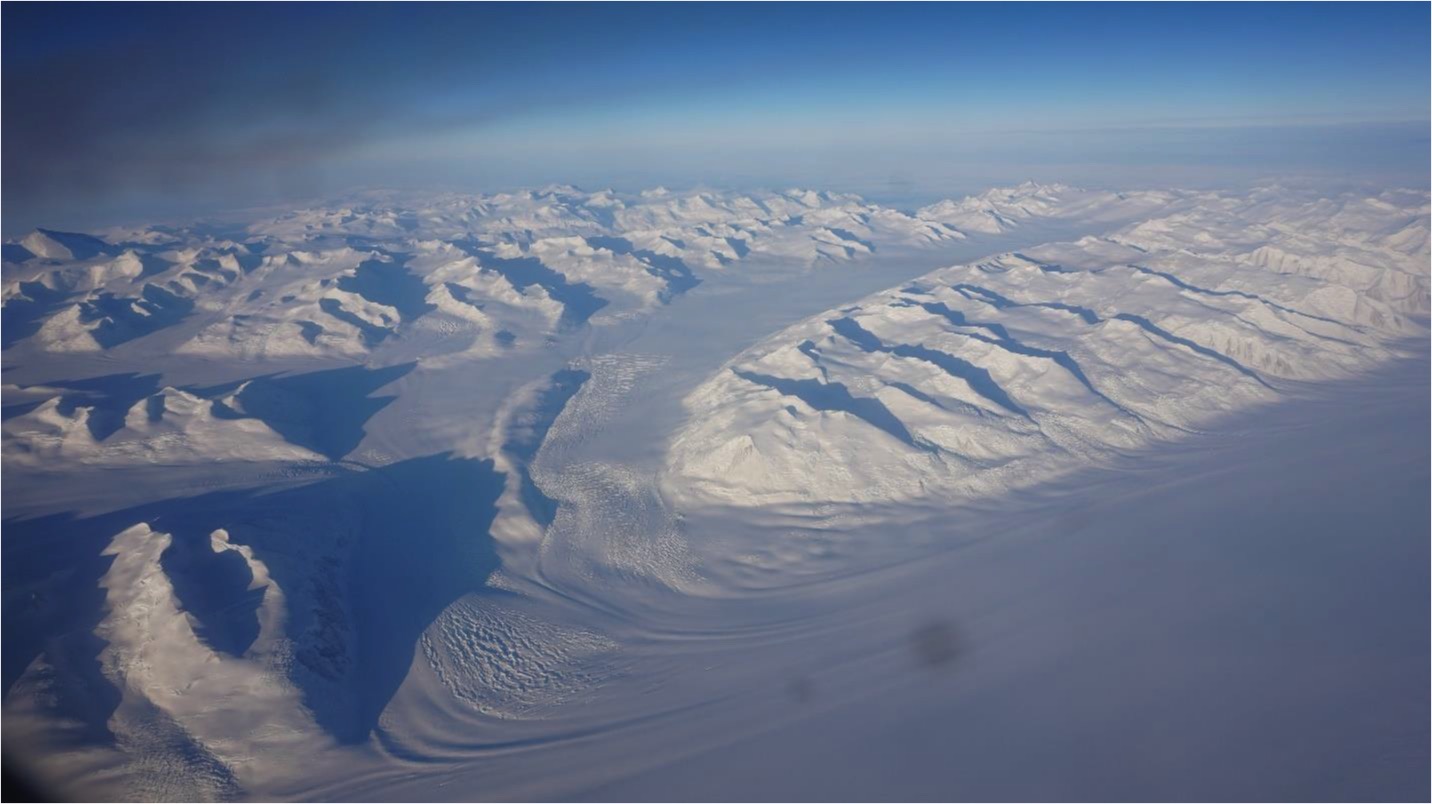

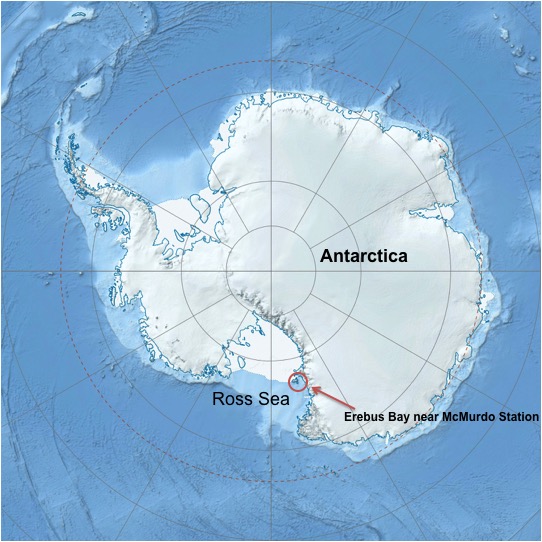

Cross with Erebus in the background. I’m sure many of the men stranded at this hut for those 20 months did a lot of praying.

Cross with Erebus in the background. I’m sure many of the men stranded at this hut for those 20 months did a lot of praying.

Recent Comments