I always find the moment surreal when you finally meet someone in person whom you’ve been following on social media for years. Tammy Russell and I had “known” each other on Instagram for a while, connected by our love for Antarctica and doing science in the field. We had both also volunteered for a SCAR campaign to blast Wikipedia with profiles of accomplished female researchers working in Antarctica. I’m happy to report the team uploaded over 150 biographies of female scientists to Wikipedia in 2016!

We had exchanged a few messages discussing our winding “late-bloomer” career paths through science, but I never thought I would have the chance to meet Tammy in person. Then, one day on Instagram, I saw that she had been invited to the Open House for prospective graduate students at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (the same school I was currently attending)! Open house is an overwhelmingly exciting time in a graduate students life and I am happy to report, Tammy will be joining the PhD cohorts at SIO this year!

I’m excited to share Tammy’s interview with you all:

What is your earliest memory of being hooked by science?

I grew up on a small farm and was always drawn to nature. I spent as much time as possible outside; catching lizards, climbing trees and watching the stars. I knew from a young age I wanted to work in science, whether that was with animals or up in space. I was really obsessed with frontiers, and for much of my childhood I thought I would be the first person on Mars. That desire to explore unknowns really cultivated a deep curiosity for the world and led to my interest in exploring the oceans and Antarctica. When I was in junior high, I attended camp at the Catalina Island Marine Institute (CIMI), and it was the first time I was exposed to marine biology and hands-on science. At CIMI, I first snorkeled, did dissections and looked under a microscope. I think that experience really solidified my motivation to pursue a scientific career.

Did you know what you wanted to study before beginning your undergraduate degree?

I knew I wanted to get a degree in Biology, and after traveling a bit after high school, I started my Bachelor’s degree at Victoria University of Wellington, in New Zealand. I did two field projects there, both on the impacts of invasive mammals on native species. These were fantastic experiences. After a couple of years there, I returned to the States, with my intent on returning and finishing my degree. But I ended up taking a very winding path and it took me many years to eventually be able to return to college. I restarted my degree at Mt. San Jacinto College (MSJC), in Southern California. After a couple years at MSJC, I was able to transfer to University of California, Santa Cruz, where I just finished my Bachelor’s in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

What was your first science-related job?

Because I have been in school for such a long time, most of the field work and research I have done has been through internships and volunteering. But I have always tried to maintain animal-related jobs: an animal hospital, city animal shelter, a reptile pet store, where I did husbandry, as well as educational presentations. I am currently a naturalist on a whale watching boat in Moss Landing, CA.

Where have you traveled with work in the field?

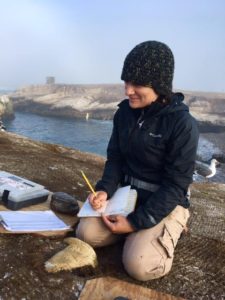

At UCSC, I was involved in Dan Costa’s Lab, working with northern elephant seals at Año Nuevo State Park. Although just north of Santa Cruz, it is another world. We went out each week to resight tags on the seals to monitor when animals were returning and how long they were staying. We also would attach and remove satellite tags and other instruments, such as accelerometers or cameras, which was always an amazing experience getting to be so close to these massive animals!

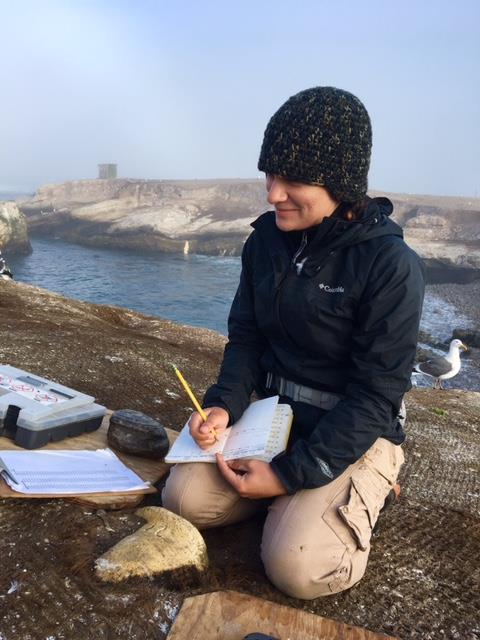

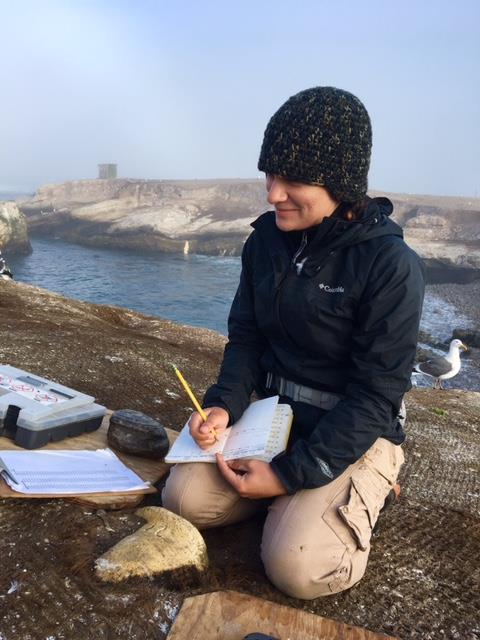

I also did an internship, and currently still volunteer, for the nonprofit, Oikonos Ecosystem Knowledge, where I have been fortunate enough to work on seabird population studies out on Año Nuevo Island. The island is strange and wonderful place. It was once home to a light tower and large home for the light tower keepers and their families, but now it has been completely taken back by the animals and is currently an important breeding location for many seabirds.

Through UCSC, I also did a field course in Sitka, Alaska. I really wanted to use the experience to try something completely different, so my field partner and I studied the effect of light levels on the red alga, Constantinea, with a combination of field observation and lab experiment. Working up in Alaskan waters in winter was truly an incredible experience (and I really valued my drivesuit!).

I am a NOAA Hollings Scholar, which allowed me to spend last summer on Oahu, Hawaii, working on the demographic distribution of black-footed albatross that are incidentally caught by longline fisheries. There, I got to learn about commercial fishing, mitigation measures to reduce bycatch and the fishery management process, as well as my research work.

What inspired you to become a scientist and work in polar regions?

When I returned to college, I had a clear idea of the kind of work that I wanted to do: I wanted to study seabirds. As I have always been drawn to Antarctica, when I started thinking about the kind of research that I wanted to pursue, my interests were inevitably drawn there. When I first started at MSJC, I did not have a lot of confidence in myself. I knew I needed to transfer from there and get my Bachelor’s, but I hadn’t really considered how to get to the research that I wanted. I fortunately met several encouraging mentors at MSJC and had an amazing support system: my husband and my mom.

I soon found myself taking on more: pursuing undergraduate research, joining honors programs, and organizing events, like birds watching trips and a TEDx event! I was really encouraged and allowed to really spread my wings at that college. The first project I completed there was on the history of women working in Antarctica and ended up presenting it at an honors conference at UC Irvine.

While at MSJC, I had tried to stay on top of research that was going on in Antarctica, and organizations that are involved in the southern region, which led me to volunteer for SCAR in helping write Wikipedia pages on women that had worked on Antarctic research, and to attend the 80th anniversary for the American Polar Society. It was there, where I got to meet people I had looked up to in conservation, breaking boundaries and research, including Sylvia Earle, Claire Parkinson and David Ainley. Meeting these, and other researchers, really corrected the image I had of scientists, and made it much more realistic for me.

Before starting at UCSC, I volunteered for a number of nonprofit and government groups doing field and lab research. I valued what I was able to learn from these experiences, but I also found that I wanted to be the one who organized the projects, I wanted to have a say.

Between these experiences and finding that the people doing the kind of research that I wanted to do all had PhDs, really made me decide that I should pursue a PhD, and that it would allow me the opportunity to do research, but also to ask the questions and develop projects to answer them.

What are some inspirational materials you’ve used along the way?

I have a notebook that I write down potential research questions, quotes, trends that I’ve observed, doodles, etc. When I feel stuck I read through it. Some entries are really funny, some ideas are totally unrealistic, but going through it always gets me thinking.

Do you have a motto you live by?

Keep throwing yourself out there at new opportunities, no matter how unrealistic they seem, some are bound to work out.

What do you envision for your future (big or small)?

Well, I’m getting ready to start at Scripps Institution of Oceanography to pursue a PhD in Biological Oceanography. It still feels unreal, it’s beyond what I could envision happening to me, so I can’t imagine where my research at Scripps will take me or where I’ll find myself afterwards! No matter what I end up doing, as long as I’m still able to be involved in research, asking big questions and attempting to answer them, then I’ll be happy!

Huge thank you to Tammy for the interview and for her entrance into Scripps Institution of Oceanography! We wish you the best of luck in your future research.

To see more photos of Tammy in the field, head over to the Feature Album on Woman Scientist Facebook page.

Please feel free to share this inspirational interview with others! Thank you all for reading and following Woman Scientist.

Share this:

by

by

Share this:

Share this:

Recent Comments