Many people who are interested in Marine Biology or Oceanography grew up loving the ocean. They have fond memories splashing in the waves, searching for sea creatures, sailing on the sea, and enjoying beach life. Not me.

When my mom was young, she almost died drowning off the coast of Washington. As a result, whenever we took family vacations to the beach, we were never allowed to go in above our knees. I was OK with that because the waters off the Pacific coast are chilly.

The only connection I formed with the ocean was one of distance. Keep your distance. The ocean is powerful. Mysterious. Confusing. Untrustworthy.

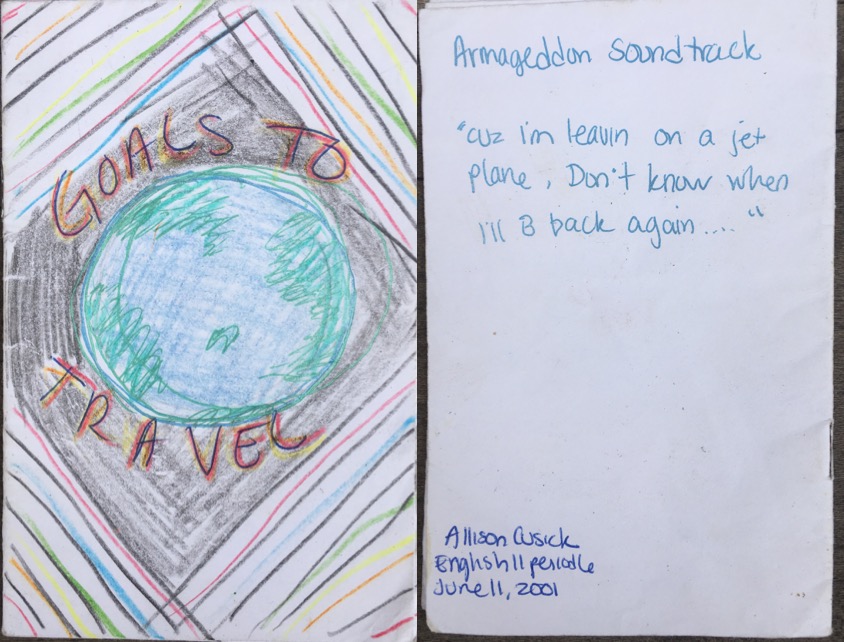

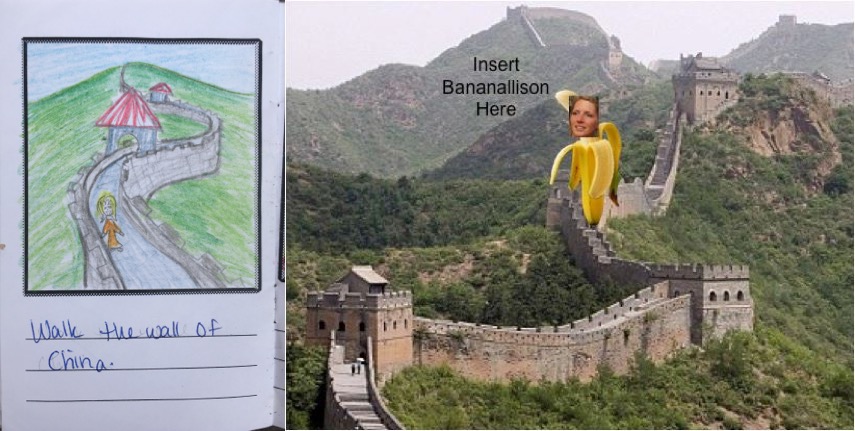

As I got older I started to ponder which career I might explore. I loved to travel and thought that being an astronaut would be cool because they traveled to the moon – the most extreme travel any human could make. I looked into the degrees that NASA astronauts got and saw that many went into science. I liked traveling and I liked nature, so I logically chose to declare Biology and Geology as my majors in undergrad.

One of the geology classes I took brought us to some islands in Washington called the San Juan Islands (near Canada). We went on the Research Vessel Centennial for a day to dig up fossils and rocks from the sea floor. Being in Washington, it was rainy, wet, and cold. I was sea sick. I was not prepared for the weather. I hated it. That day, I vowed that I would never study the ocean. Keep that distance.

Too cold. Too wet. Too windy.

Around that same time, it also dawned on me that astronauts don’t actually travel to space very often. So with my space filled wanderlust dreams shattered and my disinterest in wet ocean related science, I instead focused on becoming a biological scientist studying land animals and birds. Far away from the ocean.

I ended up completing my Bachelor’s Degree in Biology with a minor in Earth & Space Sciences (i.e., Geology) from 2002 – 2006. I then held many jobs in various fields of science afterwards. From 2006 – 2010, I worked in immunology, neurobiology, and field ecology studying birds, squirrels, and land mammals. I felt like I was wandering. Unsettled. Frustrated not finding my niche.

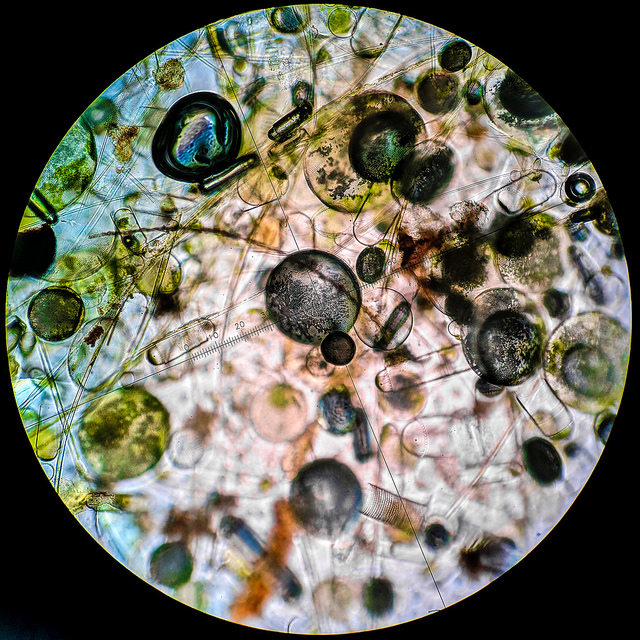

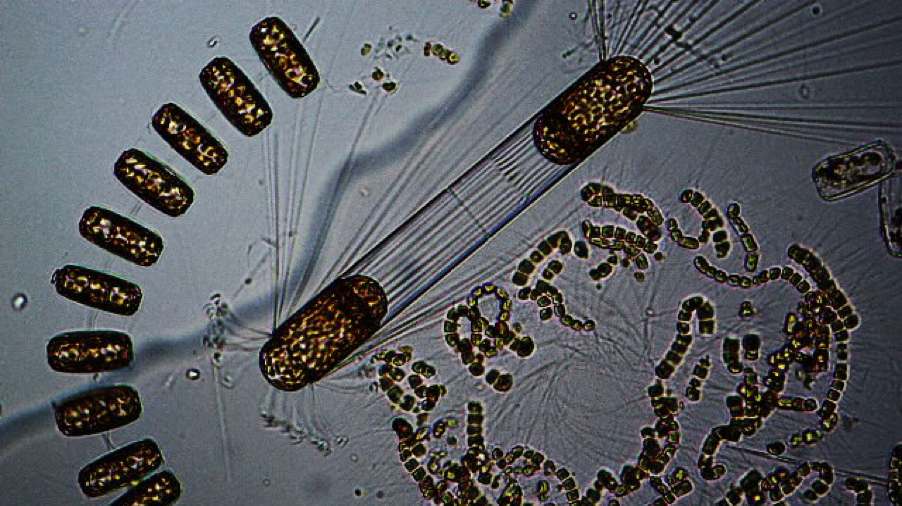

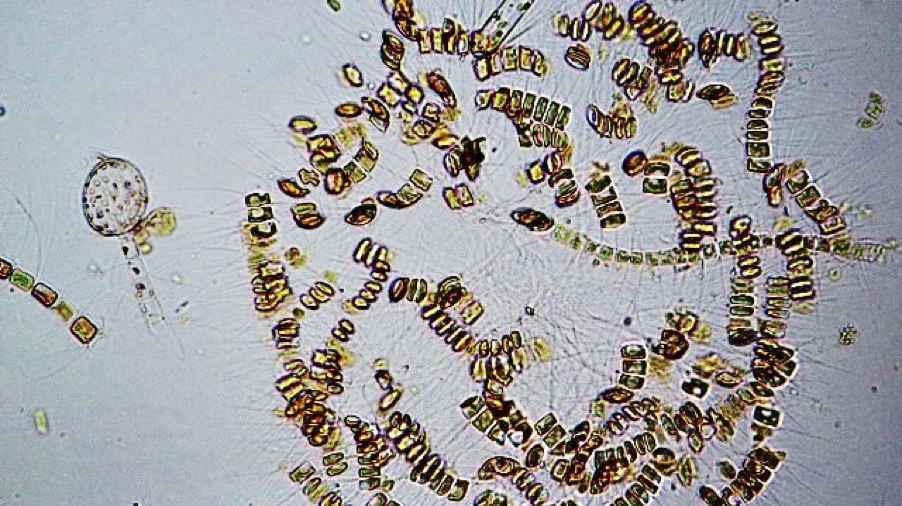

In 2010, I realized I had to leave the seasonal field biology life and I found a job working in a lab studying phytoplankton. At the time I had no idea what phytoplankton actually were. I knew about diatoms in the form of diatomaceous earth from my geology courses, and I figured I could learn what I needed on the job. I would be running experiments and looking at how phytoplankton respond at a genetic level to increasing levels of carbon dioxide (known as ocean acidification). It was a very successful research technician position and resulted in many publications.

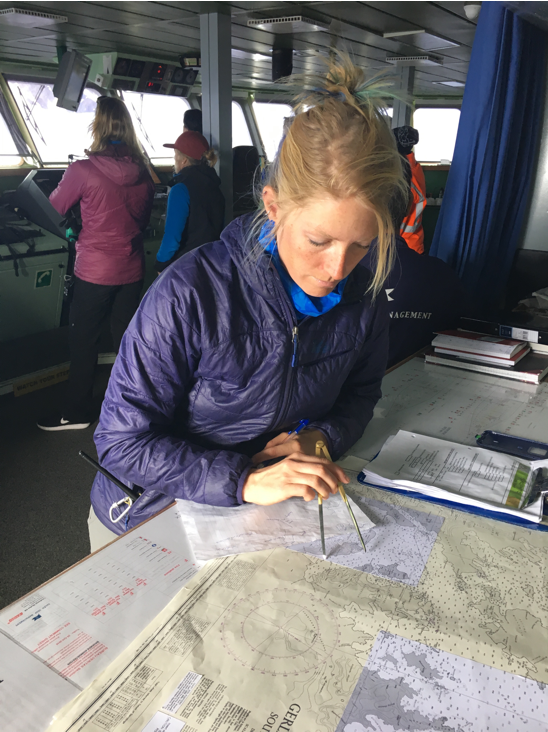

Three years later, in 2013, my boss got an offer to go on a research icebreaker to Antarctica for 53-days but she couldn’t take that much time off. Instead, she sent me. I had always wanted to travel to Antarctica, but always thought it would be as a tourist. My luck changed overnight and I couldn’t believe it. That was not in the job description when I applied three years prior!

I was going to Antarctica! And I had no idea what I was doing. I had never been at sea before. I had no idea what these giant scientific instruments did. I opened my ears and read a lot to try and absorb as much information as I could in preparation.

When I landed at the US McMurdo Station in the Ross Sea, I felt like I had landed on the moon. Antarctica felt so extra-terrestrial. My inner astronaut was satisfied. I dont need to go to the moon. I’m already on another planet! I then boarded the icebreaker (RV Nathaniel B Palmer) and lived on board for 53- days doing science with a team of researchers in Antarctica’s Ross Sea. I thought to myself, if I ever go to graduate school I will study Antarctic ecosystems. I didn’t know how that would play out back then, and I didn’t actively seek graduate school for three more years after that experience.

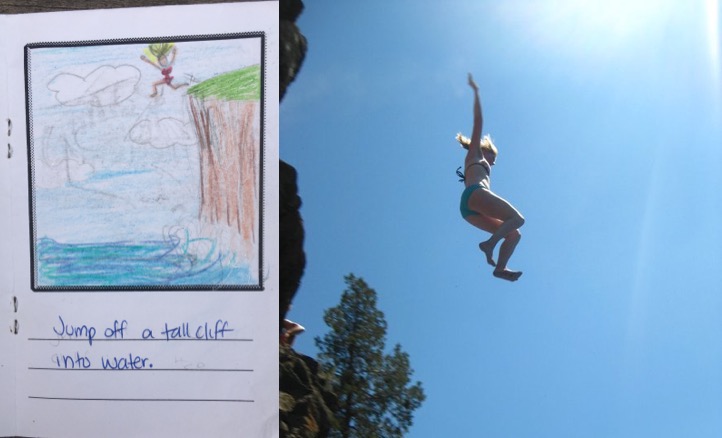

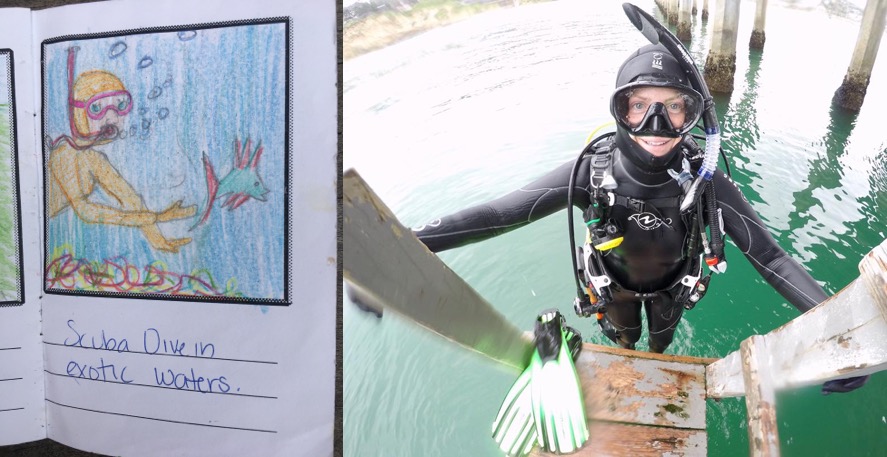

It was also during this time in my life that I tried surfing for the first time. In Washington. I fought past the breakers and sat on my board looking back toward the coastline. Holy Shit. This was the first time in my life I was IN the ocean past my knees!! Yes, I had been swimming in secluded seas, but never the ocean. Especially not the big scary Pacific Ocean that nearly killed my mom. I was 28 years old. My relationship to the ocean was slowly changing.

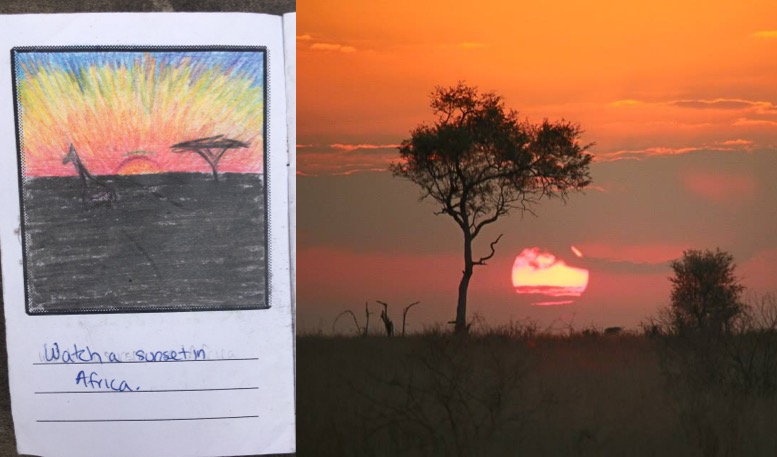

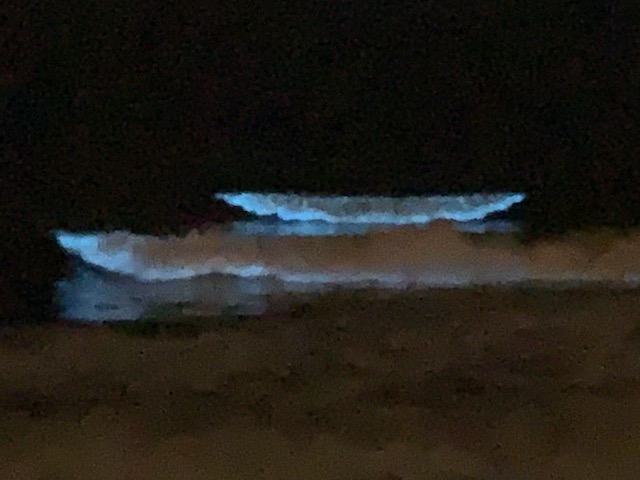

We fast forward to 2019, now I am working in the coldest, windiest ocean in the world. The Southern Ocean – the mother of all ocean currents. Frigid waters reaching 0 to -1.8C temperatures. Wind speeds that can knock you off your feet and flip a small boat. I love it. The more harsh, the more fun.

I wonder how I went from hating the oceans to loving them.

Over my experiences I learned that working on ships was really fun – and that Oceanography might not be such a bad career choice after all. It allowed me to work in the lab, work on ships, travel to extreme remote locations, and study some of the most pressing climate change issues of our time in a region of the world that is rapidly changing. It was the lifestyle of science that fit my desired niche.

During my time on board the ship, I also learned about the tourism industry and that it was growing. There was an entire community of people wanting to come learn more about this faraway land. I have always enjoyed getting other people excited about science and thought, whatever future research I do, I want to involved that community of travelers. I myself enjoyed taking vacations on “voluntourism” trips helping researchers with their work just for fun. So I knew there would be an interest within the Antarctic travel industry for engaging people in current polar science. So they could be part of the scientific legacy down on the icy continent.

In 2016 – 2017 I completed a Master’s degree in Marine Biodiversity and Conservation at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where I developed the citizen science project FjordPhyto (@FjordPhyto) and I realized, to keep doing this work, I needed to go in to the PhD program. Today, third year into the PhD program, I find myself doing so many things I had dreamed of doing all wrapped up into one. My early 20’s self, who specifically wrote off Oceanography because it was cold wet and windy, is now specializing in the biology of polar oceans.

The oceans remain powerful and mysterious to me, but confusion and distrust have turned into reverence and awe.

Its been quite the unrealized career dream come true. A haphazard path to get where I am today. If I had any advice to give young students, I would say allow yourself to explore. Explore as many options as you can. Dont feel locked in to one type of science or one job. Try things out. Dont write anything off and if you do change your mind, you can always start over or start new, if you want. Keep your options flexible and above all, at least make sure to find passion in what you’re doing.

Thanks for reading!

If you’d like to read other posts I wrote about my career path check these out:

Recent Comments